Mystery

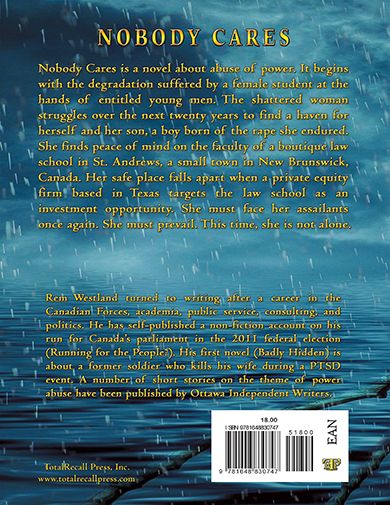

Nobody Cares

CHAPTER 1

I

n the last week of April, at the start of what would be a hot spring, the Saint John Chronicle in the Canadian province of New Brunswick featured a series of podcasts on the Beta Eta Epsilon fraternity and its “Greek Life” parties. Online readers had, for months, been bombarded by reports on climate change, new mystery diseases uncovered in Africa, and the continuing impact of a pandemic that a former US president said would disappear in 2021 if he were re-elected. This was the first time most SJC subscribers had ever heard of the BEE. The shift in focus, from global to personal, and the subject matter was tantalizing.

Jessica Winslow’s recurring nightmare gathered force the night after the first of the podcasts was released. The brutish delight of inebriated men, the diminishing cries of protest from helpless women, the groping, the grinding, the hurting. Most of all, Jessica continued to envision a row of large white teeth, with one that was missing on the upper right beside the man’s eyetooth. But she could handle it. Her life, in the town of St. Andrews on the Passamaquoddy Bay in the southwest corner of the province, was pretty good right now.

She had learned to wake herself before drifting back into the trauma of that evening. Her eyes, springing open on the command of the missing tooth, would zone in upon the academic awards displayed in prominent places on the walls of her bedroom. Her bachelor of arts from the University of New Brunswick. Her law degree from that same university. She would awake to pride rather than shame. Determination, rather than fear.

She picked up her pen.

***

The BEE, as the fraternity had been known since its founding in 1904, was a club to which Daryl Arnett, a graduate of a law school in Florida and now a ranking American senator, had once belonged. For days he swore under oath he had never heard of any so-called toga parties. Then came the allegations in an unsigned letter. The anonymous writer described an orgy that had victimized a dozen female students.

People say we all consented, the writer observed. But the women did not know about the drugs. I will never forgive myself. Daryl Arnett was there. At the very least, he should acknowledge what happened. He should be man enough to apologize.

The new president of the United States had tagged Senator Arnett to become secretary of state even before the primaries were over. Arnett was regarded as a sound choice, one of the many sound choices the president was making. She was determined, after the allegations surfaced, to keep fighting for the Arnett appointment. She wanted the senator on her team. He was a family friend.

Arnett had made his name as a member of the Senate’s Committee on Foreign Relations. A vigorous man of forty-six, with a physical form and youthful appearance honed by regular workouts and Kennedy hair, Arnett had a network of close associates all over the world. Many of his friendships had been established through the BEE. He had been effective in helping one American administration after another, Democrat and Republican, resolve misunderstandings between countries in ways that only a person well plugged into the families of the global elite could have done.

The words used to describe Daryl Arnett were kind, good humoured, trustworthy, sincere. The charisma he exuded, and his power, attracted women to him as well as men. He was driven. He was successful. There had never been a whiff of scandal.

The letter alleging that Arnett had participated in an orgy generated a frenzy of research by political staff. For how many years had the males-only BEE victimized women? While the victims were shattered, how many men had gone on with their lives as if nothing had ever happened? Was there a link between the shenanigans in Florida and a Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into Greek Life parties at Penn State some ten years earlier?

The president asked the FBI to resuscitate their inquiry and to dig deeper into Arnett’s background. Politically there was no choice.

“Stay focused upon the senator,” she instructed. She did not want a witchhunt. “Start with Daryl’s graduation year.” Her husband, three years senior to Arnett at the same law school, had been a “brother” as well.

When a draft of the Bureau’s report was leaked, containment of the investigation to schools in Florida and Pennsylvania was no longer possible. The public learned that toga parties were a long-standing tradition of the BEE at all of its chapters and that sexual assaults were a long-rumoured feature. In his graduating year, Senator Arnett had indeed participated. The senator’s nomination was withdrawn, but the witchhunt the president had worried about was only beginning.

***

The FBI report, with the title “Sexual Assault at Universities in America,” named no names. It documented allegations of BEE assaults, ranging from one-on-one abuse to gang rapes, at every one of the universities and colleges hosting a chapter of the fraternity. Allegations were grouped by state, not by institution.

At the White House, two FBI agents—Paula Johnson, a severe-looking woman with a tight blond bun, and Gordon Fletcher, in his late forties with sandy-brown hair turning to grey—sat stand-by on stiff wooden side chairs outside the door of the office of a young staffer in the president’s communications group. The FBI’s acting director, Bryan Ford, sat impatiently in a comfortable armchair in front of the staffer’s desk. He did not like the political drift the investigation was taking. He was anxious to get back to more important work at his office in the J. Edgar Hoover Building.

The staffer, Greg Radzenko, had long blond hair, blue eyes, open-collar shirt, jeans, and a languid air. The hundreds of bound pages of the draft FBI report sat heavily on his desk while he skimmed the executive summary in PDF on his computer.

“Where is the name of the whistleblower?” asked Radzenko.

“We don’t name names in our report, Mr. Radzenko,” said Ford, whose big ears twitched when he spoke. “We don’t know the identity of the whistleblower anyway.”

But you damn well know most BEE alumni are Democrats, thought Radzenko. The FBI, lambasted for its alleged Republican sympathies, were on the hit list of the new political regime in Washington.

“Why do you not accept the undertaking of Mr. Oliver Kahn?” Radzenko asked. He did not look up. “As president of the BEE Alumni Association, he speaks for that entire community. They were all just kids, having fun. The association funded a study that proved it.”

Oliver Kahn, CEO of the second largest engineering consulting firm in the United States, had used a guest column in the New York Times to answer extremely bad press regarding the BEE. He assured in elegant prose that toga parties had always been consensual among participants. He guaranteed that, in light of changing times, the parties would never happen again. He asked university presidents, in return, to have the FBI stop their pursuit. We and the universities can resolve the matter together, he wrote. We do not need governments.

“Why dredge up the past?” asked Radzenko. “The BEE alumni are very important people. They are livid about all this.”

“A strong message is needed,” Ford replied. In his very person, he emphasized the word strong. He looked like a middle-aged United States marine, as fit today as he was when he graduated from boot camp at Fort Benning.

“The BEE alumni want bygones to be bygones,” said Ford. “But that’s not good enough, Mr. Radzenko. Student groups with a BEE chapter on their campuses might have accepted this a decade ago but no longer.

“The students today want change. A strong message is needed,” Ford added.

“Really?”

“Don’t mock me, Mr. Radzenko.”

“I’m sorry. I don’t think anyone cares. The hype around this will die if we let it. Economic fallout from the pandemic will be top of mind for years yet.”

“The details will hit some of the women very hard,” said Ford. “They will know if their own experience is the one being described, and they will take action. In states where there is no statute of limitations, some of the complainants are certain to get a hearing in court. The rape culture was a pandemic in its time. The women who go to court will put well-known faces on their assailants.

“If the BEE is slapped on the wrist by the FBI, our Bureau will have sent a message that light treatment is acceptable. Public prosecutors are calling for stiff sentences. The Bureau will be embarrassed.” Ford did not like being bullied.

Radzenko swivelled his chair away from the computer.

“Let’s get back to the whistleblower,” he said. “The new president is angry. Senator Arnett’s career is finished. The man has been destroyed.”

Ford looked at his wristwatch.

“At a time when a woman can be president, when so much has changed, why give a pass to a person who has done such harm anonymously? We want the name! In your memo, you refer to a professor who researched this stuff. The Arnett letter was not the only one?”

“She learned of two additional letters.”

Ford called for his two agents, Fletcher and Johnson, to be brought into the room.

“Two other BEE alumni from the senator’s year were targets as well,” affirmed Agent Fletcher. Unused to being inside the halls of power, his long and skinny frame trembled as he spoke. Ford looked impatient.

“No, there’s at least one more,” Agent Johnson corrected her colleague. “That makes four altogether, counting Arnett. This last one is pretty serious.”

Ford nodded in support.

Johnson reached into a purse large enough to double as a briefcase and pulled out a single page of paper. She handed it to Ford. This was the letter he wanted to see.

“This one is tied to the suicide of a member of the House of Lords in Britain,” said Ford. He slid the page across to Radzenko. “Richard Brennan. He was a member of the BEE and a participant at the same toga party. The original went by snail mail to the chairperson of the board at Wilson Financial, a private equity firm in London. Brennan had been named to the board a week prior to his death.”

***

To: Elizabeth Greer

Chair of the Board

Wilson Financial

London, GB

I am aware that Wilson Financial has named Lord Richard Brennan to its Board of Governors.

Richard studied for his law degree at Florida’s Logan School of Law in the United States. While there, he was a member of the Beta Eta Epsilon fraternity. The BEE, Ms. Greer, is a self-selecting group of entitled men whose attitude to the world around them is, in a word, rapacious. I have been tracking the careers of BEE alumni.

Perhaps Wilson Financial sees nothing wrong with squeezing profit and pride from others, as long as Wilson Financial gets the money it wants? But there are limits, Ms. Greer. Richard Brennan exceeded those limits.

In his graduating year, Richard—whom we knew as Dicky—participated in a toga party. The women invited by BEE members were drugged unconscious and raped. After the men had stripped them of everything, the women were abandoned. They were left by their male partners to find their own way home. The new member of your board is that kind of man.

If you decide the appointment will stand, Ms. Greer, I will share this letter with the British press.

(Copy sent to Lord Richard Brennan.)

***

“All four letters are essentially the same,” said Ford.

Acting Director Ford and his two agents gathered their papers together, preparing to depart.

“By the way,” said Ford pausing briefly. “From here on, the attorney general for the state of Maine will be taking the lead. The FBI is shifting to a support role. Fletcher will email you the details.”

“Hold on a second, Director.” Radzenko stood up from his chair, leaned across the desk, and placed a hand on Ford’s arm. “Why Maine?”

Ford looked with a frown at Radzenko’s hand on his sleeve.

“The letter that targeted Lord Brennan was posted from somewhere in that state.” Ford shook his arm free and stood fully up. “The Florida U professor you mentioned got hold of an envelope with the address of a BEE alumnus written in longhand. It had been posted from Maine as well. By coordinating our follow up through Maine’s justice department, we avoid questions about FBI jurisdiction. The White House has an ongoing interest but is no longer in charge.”

“So, one of the ladies has been getting her revenge?” said Radzenko with a grin. He flopped back into his chair.

The FBI acting director turned at the door and looked stern in reply.

“Mr. Radzenko, Lord Brennan was a married man, good reputation, three children. You may see his suicide as deserved retribution. You may think this is funny. The police in London see it as someone exercising a power of punishment that she does not have. That’s why there are laws. The British government has asked for this country’s cooperation in the investigation of a criminal act. They will have it.”

Radzenko shrugged at the reprimand and rolled back from his desk.

“We will continue to liaise with the international police services. But if you need help with your clever press releases, don’t call us. Call Maine. Fletcher will send you the coordinates.” Ford spoke dismissively. He did not expect to survive the culling of alleged Republican sympathizers anyway.

The hunt was on. The whistleblower would be exposed. The culprit would be punished.

Ford’s agent Paula Johnson was the one to whom the opened envelope had been given. The professor at Florida U who gave it to her had included an extensive note. Please keep this confidential, the professor wrote. If identified, the whistleblower’s life will be at risk. Johnson filed the note between two books on her library shelf at home.

CHAPTER 2

J

essica Winslow began every day by dousing her nightmares with coffee, savouring her good fortune, and writing her dreams in a diary. On this fine morning, immediately after coffee, she prepared for the arrival of her only regular visitor.

Her heritage home in St. Andrews—built in 1831 and known to locals as “Rosedale”—sat on a sloping, fully landscaped double lot on a quiet street within the historic town plat.

Jessica, who lived alone with her twenty-one-year-old son, Adam, did not really need the five bedrooms, though they allowed her to easily accommodate her mother and father when they drove the hour and half from Fredericton, New Brunswick’s capital city. She had given up using the two wood-burning fireplaces in the double parlour because of all the trouble, and she rarely sat on the elegant front porch from which, through the leaves, she could see the Passamaquoddy Bay a half-kilometre down the hill.

On the day she took ownership, when Jessica looked up from the corner of Edward and Carleton Streets to gaze upon her new home, one of the more gracious houses in St. Andrews, she felt—for the first time in decades—safe. Being able to afford Rosedale had tipped the scales when she was offered a job at the newly opened St. Andrews School of Law.

At St. Andy’s, as the school became known across the three Maritime provinces, Jessica had been hired to teach property law. It was the area of law her father had specialized in as well.

In ten short years, St. Andy’s had become one of the best law schools in Canada. Two years into her employment, Jessica was the school’s dean of law when St. Andy’s made it to number three on a nationally ranked list maintained by Maclean’s, one of Canada’s national magazines. Law schools at the University of Toronto and at McGill came first and second. The law school at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, Jessica’s alma mater, was far down the list.

***

The worldwide collapse of stock markets in 2008 had exposed the vulnerability of countries and regions where money spent by tourists contributed to half and more of the GDP. The opening of a boutique law school in St. Andrews in 2010 was a response to that collapse. The provincial government of the day wanted to broaden the economic base of Charlotte County.

The provincial government had used the Appalachian School of Law in Virginia—a boutique law school in another relatively isolated location—as a precedent for St. Andy’s. Focused upon environment and community service, the Appalachian School of Law had been established in the small town of Grundy, in Buchanan County, with an eye to the economic development of the town and its region. Students were recruited from all over America with the hope that some, upon graduation, would stay in the state to become community leaders.

St. Andy’s brought with it a student and staff population of four hundred. Those four hundred new residents joined a community already hosting students and teachers from St. Andrews campus of the New Brunswick Community College, the Sir James Dunn Academy, the Vincent Massey elementary school, a couple of research institutions focused upon oceanography and fish, an aquarium, fish farms, and a newish social centre—the O’Neill Centre built by Aiken family money—that featured a theatre and two ice rinks, one for curling and one for hockey. Just about every permanent resident was cogged into one or more of the wheels that kept St. Andrews turning.

The online account of St. Andy’s survival through the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic had gone global even before the virus began its retreat. The school not only survived: it prospered.

***

The table on the first landing of Jessica’s Rosedale was elegantly set. Jessica had put out crystal wine glasses, properly set china and cutlery, napkins, the works. The aroma of Jessica’s seafood chowder permeated the room. The buns heating in the oven had been purchased that morning from Kelly’s Bakery at the town’s wharf.

“So, what’s the occasion?” asked Gail Hinge as she breezed through Jessica’s unlocked side door.

Their decade-long relationship had begun the day after Jessica moved in from Montreal.