War & Military

The Letter

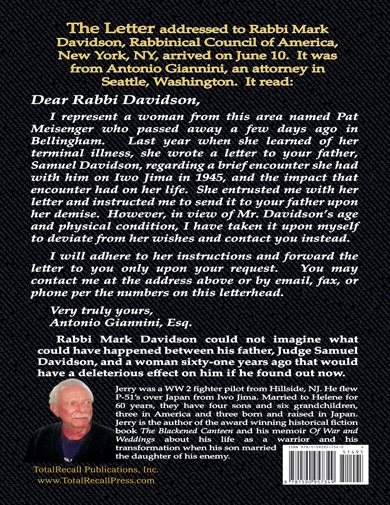

Rabbi Mark Davidson could not imagine what could have happened between his father, Judge Samuel Davidson, and a woman sixty-one years ago that would have a deleterious effect on him if he found out now. Judge Davidson was eighty-two, in good health, had all of his mental faculties, and did not shock easily. As an attorney and judge, he had seen, heard, and been part of many bizarre cases and experiences. The Rabbi was inclined to pass this letter on to his father and let him deal with it in his own way. His training as a Rabbi always made him think how best to stay out of people’s private affairs and guide them to self-made decisions. This, he determined, might not be a situation that would allow him to do that, so he decided to call Mr. Giannini.

Their conversation was cordial at first. Mr. Giannini knew about Rabbi Davidson through the prominence of his father, Judge Davidson, and the little publicity the Rabbi had generated about himself as an outspoken proponent of women’s rights and other issues unpopular with the current administration in Washington. At first, Mark was suspicious of Mr. Giannini’s tone. However, the talk became much friendlier when Mr. Giannini volunteered that he was in agreement with much of what the Rabbi thought and stood for.

“I never read the letter, Rabbi; I only know that my client had written it recently. I was asked to represent her by a former priest from my Parish. I know the letter is quite lengthy and the sealed package may also include a few pictures.” Mark asked him to mail it the next post and he said he would send it Fed-Ex that afternoon.

Two days later the package arrived at Mark’s office. Mark found it on his desk when he returned from visiting congregants in the hospital. It was late afternoon and he did not know if he had the energy to finish writing his sermon, and then read what might be a difficult letter, before leaving for home. Curious, he opened the package. Attached to the outside of the envelope addressed to Samuel Davidson was a small, faded picture of his father as a twenty one year old fighter pilot with a young woman. "Pat and Sam, July 9, 1945, Iwo Jima" was inscribed on the back of the photo. His hands began to tremble as he held the picture, and he wondered if he was doing the right thing. Should his father be opening and reading the letter? Should he have held off having the package sent, or even ignored Mr. Giannini’s letter? As these questions bounced around in his head, he carefully opened the envelope and felt the heft of the typewritten pages.

The Letter

Dear Samuel, I am writing this letter to you 60 years after I should have written it and after years of hesitation. What prompted me to do it now is the knowledge that I have only a few more months to live and I felt that you should know the impact our brief encounter had on my life. I really do not even know if you will remember me after all this time, so I have attached a picture that I have held close to my heart ever since it was taken on July 9, 1945. I remember the date so well; it was the day after I arrived at your airfield on Iwo Jima as part of a small USO troop called the Winged Pigeons. There were four of us, two girls and two guys, musicians and dancers sent to forward bases to entertain as best we could and bring a little home to the soldiers.

We watched as your squadron returned from a mission over Japan. What a thrilling sight it was as you buzzed that dirt airfield, peeled off in groups of four and landed. That evening I was walking along the flight line and you were sitting on the wing of your P-51, smoking a cigarette, and staring at Mt. Suribachi. I had never seen a more forlorn look on such a young, handsome man. I stopped, jangled your foot and when you looked down I said,

“Hi, I’m Pat Meisenger from Bellingham, Washington, how are you?” You seemed to come out of a trance, jumped down, stuck out your hand, and said, “Sam Davidson from Newark, nice to meet you.”

I wanted to know more, so I asked, “Who is Lilly D?”, the name on the side of your airplane. That began a conversation and led to a walk to a burnt out pillbox overlooking the ocean. We were on top of that pillbox all night while you told me about Lillian, your plans to get married, the mission you had flown that day and the loss of your two squadron mates, Al Sherren and Pudgy Carr. You were so sad. My heart filled with an overwhelming desire to hold you, console you. When I moved closer, you responded to my touch. We made love that night and I felt gratified that I had given myself to you even though I knew that it was my prompting, not you that made it happen.

I flew to Guam the next afternoon and did not return to the States until mid-August, the day before the war ended. I returned to Bellingham a few days later and discovered I was pregnant. My family raised me as a Catholic and I believed all that I had learned and practiced my entire life. I knew that my condition would destroy my mother and father and my oldest brother who was a priest. I knew that I had to deliver my child, our child, and I knew that I could not tell you or keep the baby. Perhaps it was a mistake not trying to find you and tell you after the baby boy was born, or even asking if you and Lillian wanted him, but that is not what I did. I also knew that I could not stay in Bellingham so I told my family that I was going back on the road with a USO troupe and flew to San Diego where my cousin Katherine lived.

Her new name was Katherine Meisenger Flowers; she had married a Marine officer in 1942. Her husband, Barry, was the scion of a very wealthy, influential Texas family. His wounds from the battle on Iwo Jima were devastating and he was recovering at the Naval Hospital in San Diego. The doctors told Kate that he would be OK in time, but he might not be able to have children.

I called Kate, told her I was pregnant, and asked her if she and Barry might take my baby. Kate was very excited and when Barry said yes but with conditions, I moved in with Kate to wait for the birth. Barry’s conditions were in line with his and his family’s very strong feelings about religion. They were fundamentalist Christians to the core with strong anti-Catholic and Jewish prejudices. I was desperate and agreed that I would give birth without revealing who the father was. Kate had to agree that if she and Barry were ever divorced that Barry would retain the baby and it would not be raised as a Catholic. Worst of all, Kate, and I would not be able to have any contact. Had I known all of this beforehand I might not have consented to the arrangement with Kate and Barry.

Kate told me that she heard Barry’s father Peter say to him “There are only two good Jews in Texas, Neiman and Marcus, and if it wasn’t for that Jew-loving Roosevelt you wouldn’t be sitting in a wheelchair but would be down on the ranch chasing woman like I did at your age and becoming a man.” Can you imagine a father saying that to a young Marine who had given so much to his country in a war? It is no wonder that there is so much hatred in the world. It is passed down from family to family, generation to generation, and no one seems to stop and think about it. They just accept everything as the truth without thought.

Years later Kate told me that the Flowers were relatives of the Goldwaters of Arizona and that Barry was named after the Senator. They must have known that the Goldwater family had Jewish blood running through their veins and yet they carried and passed on all of the hatred of generations. What would Preston, Barry’s father, have done had he known that Barry’s adopted son was not only Jewish but Catholic too?

Our son was born on April 1, 1946 in San Diego. I have enclosed a copy of the birth certificate for you. The doctor told me the original was destroyed and a new one naming Barry as the father replaced it but he did give me a copy of the original. I had him in my arms only a few hours but I loved him with all my heart, and much of my life since has been lived with sadness. If only I had been able to see you, talk to you. They named him Adam.

I have followed your career, Samuel. I read your book Memories of War and saw you on 60 Minutes with Mike Wallace. I know about your family and how proud you are of them and how grand it is to hear you say that you have been married for 60 years. I saw Adam once when he played tennis in Burlingame, California. He reminded me of how I remembered you, so young and handsome. Your son Mark was there too, but I did not want to meet him.

Those few moments of bliss that we had has sustained me all my life and I am grateful that they were with you. I am not afraid to die nor do I regret my life. I do regret some of what Adam stands for and wonder if he knew the truth would he have taken the path he chose? I wonder, too, if Barry had not been so hard a taskmaster if Adam would have become so dogmatic and unbending in his belief in Jesus and Christianity being the only route for salvation. Kate told me that Barry was not the same man after he came home from the war. He drank heavily and was very bitter about his wounds. I guess many veterans felt that way.

Kate wrote me every month with news about Adam. I kept those letters in a box under my bed and read them repeatedly as the years went by. I had so many that I bought a computer and rewrote them onto a disc, the printout is attached.

The letters stopped coming in 1967. I was frantic and after 4 months, I called Kate’s house in Austin, something I had promised myself I would never do. I asked for Kate and was put on hold. The young man’s voice said, “This is Adam.” I gasped for breath and told him this is Patricia Meisenger, a distant cousin of your mother. “You must be distant,” he answered, “I never heard of you. She’s dead, died 4 months ago.” His voice was so cold, heartless that I could not talk; my hands were shaking so much I had to put the phone down. I do not remember how much time passed, but when I picked it up the dial tone was beeping. I made it to my room and I think I fainted. When I came to, I had to speak to someone so I called our priest, Father Carmody, and asked if he could hear my confession. I told him the whole story and for the first time since Adam’s birth felt like a burden had been lifted. Now someone besides Kate and Barry knew. I told Father Peter that I had to have a way of knowing about Adam and he told me not to worry, he would take care of it and help me keep my secret. He did, too, his notes are also on the disc.

About five years later, I had built a wonderful relationship with Father Peter; he told me he was leaving the priesthood. His reasons were, for him, simple and concrete, his principles regarding religion and politics. His father, General Carmody, was involved in making decisions regarding the conduct of the war in Vietnam. As a military man, he followed the dictates of his President with no regard for his own personal feelings. That was his job. Father Peter was opposed to the war, the indiscriminate bombings of innocent people, the reasons we were told we were there, and he had a very long record of supporting the opposition in silence. After a confrontation with his father, he knew he could not be silent any longer and that meant he could no longer remain a priest. He told me that he would fulfill his promise to keep me informed about Adam and he did.

Dear Samuel when he found out that I was so ill he came to see me and told me that he knew you and your family well. I learned about his friendship with Mark and how close they were. He was very fond of you, Lillian, and your family. He had kept that to himself for so many years, never once hinting that he even knew you. He introduced me to an attorney who helped with my will. I also gave Mr. Giannini this letter to mail to you after….I was gone. How strange the workings of God that we should have such a connection.

Even now, we are still at war, still having so many young soldiers dying and suffering the effects of combat I am almost glad that my time on Earth is ending and that I will not have to read about the terrible ills that man brings to the world.

I do not know what you will do about this letter, Samuel. I do not even know if you will ever see it. If you do read it and decide to share it with your family or even with Adam I would like you to tell them I have, in one short encounter with you, fulfilled my being as a woman and that fulfillment has sustained me all of my life.

Goodbye and thank you

Pat Meisenger

June 10

After Mark read the letter, he had a difficult time deciding what to do. It was so powerful, so touching and possibly so devastating to all concerned that he even thought of destroying it. Days later, and from his memory of that day he told his three brothers, Alan, Jay, and Lee, “I was stunned by the contents of the letter. Learning that Adam Flowers was our half brother was devastating, a Christian Republican was hard to accept. Equally astounding was learning that Peter Carmody was involved. Peter was a learned writer very much in the news from time to time. I had spoken to him a few times over the years. When a new book of his came out or an editorial he had written became national news, I would call and congratulate him. Our youthful friendship did not go beyond that since we were too busy living our own lives. But now our lives would be intertwined, I needed his help and his advice so I picked up the phone and called.”

“Mark, I have been waiting for your call, how good to hear your voice again.”

“How did you know I would call, Peter?”

“I introduced Pat Meisenger to Antonio and we discussed it several times and decided you should receive the letter, not your father.”

“Antonio?”

“Antonio Giannini, Pat’s attorney.”

“Oh. Peter, this letter, we need to talk. Can we meet somewhere?”

“Sure, it will be good to see you. Where and when?”

“New York, Boston, you tell me.”

“I’ll come down to New York, Mark. Get me a room, will you please?”

“No need for a room, friend, we can stay together in my parents' apartment.”

Part One

Chapter One

Mark Davidson became acquainted with the impact religion has on politics in the election of 1960. Jack Kennedy was running against Richard Nixon and Kennedy’s Catholic upbringing was getting a lot of press. Mark was 13 at the time, living in New Shrewsbury, New Jersey, and preparing for his Bar Mitzvah with Rabbi Arnold Ross at Temple Beth Shalom. His father Samuel, a lawyer and local judge, was not a religious man, but he insisted that all four of his sons attend Hebrew school and become Bar Mitzvah as well as attend Sunday school. Samuel, Lillian, his wife of 16 years and their two oldest children, Alan and Mark, regularly attended Friday night services. At a service in October 1960, Rabbi Ross announced that his sermon the next week would be “Can a Jew Vote for a Catholic to become the President of the United States?”

Samuel gasped as soon as the Rabbi’s words were spoken, “No, he can’t do that.”

“Why not, Samuel?” Lillian whispered.

“It is not a subject only Jews should hear, Lillian. The Rabbi has to share his opinions with the entire community. I must ask him to reconsider.”

When the services ended and the receiving line was empty Samuel approached Rabbi Ross with extended hand and spoke to him in a gentle voice, “Lovely sermon tonight, Rabbi, as usual.”

Rabbi Ross smiled, took Samuel’s hand in his and said, “You say that every week, Samuel, and then you either add your opinion or ask me to do something. Do you have something on your mind tonight, too?”

“As a matter of fact, I do. About your sermon next week, Arnold, I think you need to make it in front of the clergy and leaders of our community, not just to our congregation. I would like you to consider postponing it for three weeks, give me a chance to contact the newspapers, get some publicity and speak to a few of my friends.”

“But you don’t know what I will say, Samuel.”

“Don’t need to know, Arnold. If religion is going to become the determining factor in our elections, it is an American issue, not a Jewish issue. I for one will listen intently to whatever you say and I would expect the entire community has a stake in your thoughts too.”

Rabbi Ross nodded in agreement as Samuel spoke and replied, “You have your three weeks, Samuel.”