My Enemy's Face

Terry Moran

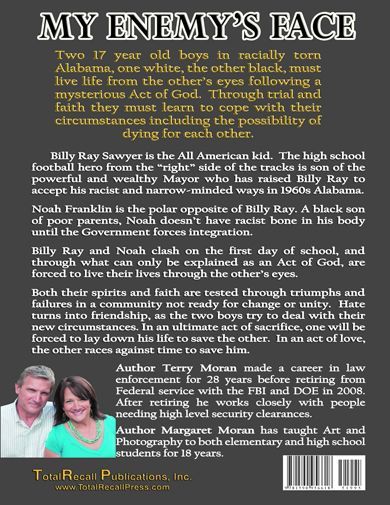

Margaret Moran, a native of Knoxville, Tennessee, attended the University of Tennessee and graduated with a degree in Graphic Design. Margaret has taught Art and Photography to both elementary and high school students for 18 years. Terry and Margaret met at the University of Tennessee and were married in 1981. They lived in Nashville, TN, and Oklahoma City, OK, before coming home to Knoxville. Terry and Margaret have three sons, Ryan, Mitchell, and Taylor.

Terry Moran made a career in law enforcement for 28 years before retiring from Federal service with the FBI and DOE in 2008. He lived in Alabama from 1961 to 1967 where his father was a Special Agent with the FBI. Terry remembers his father working multiple civil rights cases involving members of the Ku Klux Klan. After retiring he works closely with people needing high level security clearances.

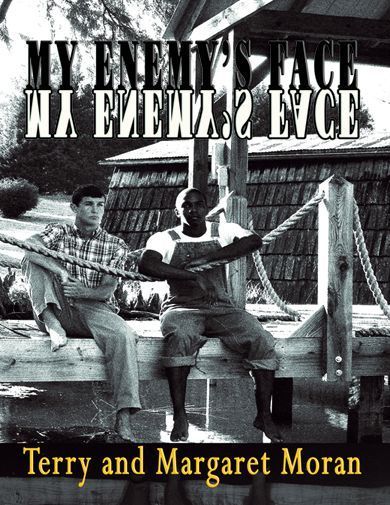

Billy Ray Sawyer is the All American kid. The high school football hero from the “right” side of the tracks is son of the powerful and wealthy Mayor who has raised Billy Ray to accept his racist and narrow-minded ways in 1960s Alabama. Noah Franklin is the polar opposite of Billy Ray. A black son of poor parents, Noah doesn’t have racist bone in his body until the Government forces integration. Billy Ray and Noah clash on the first day of school, and through what can only be explained as an Act of God, are forced to live their lives through the other’s eyes. Both their spirits and faith are tested through triumphs and failures in a community not ready for change or unity. Hate turns into friendship, as the two boys try to deal with their new circumstances. In an ultimate act of sacrifice, one will be forced to lay down his life to save the other. In an act of love, the other race

Billy Ray Sawyer is the All American kid. The high school football hero from the “right” side of the tracks is son of the powerful and wealthy Mayor who has raised Billy Ray to accept his racist and narrow-minded ways in 1960s Alabama. Noah Franklin is the polar opposite of Billy Ray. A black son of poor parents, Noah doesn’t have racist bone in his body until the Government forces integration. Billy Ray and Noah clash on the first day of school, and through what can only be explained as an Act of God, are forced to live their lives through the other’s eyes. Both their spirits and faith are tested through triumphs and failures in a community not ready for change or unity. Hate turns into friendship, as the two boys try to deal with their new circumstances. In an ultimate act of sacrifice, one will be forced to lay down his life to save the other. In an act of love, the other races against time to save him.

To Grace Lewis and Jo Moran Sayers, our greatest encouragers, and to Ryan, Mitchell and Taylor who bring us joy every day.

In memory of our dads, Bob Moran and Richard Lewis.

enemy, black, white, football, racism, prejudice

67000

Thank you Laschinski Emerson, for your help in validating our account of the pain caused by racism.

Thank you to Anne Jaeger and Sara Baker for your help in the editing process.

Two 17 year old boys in racially torn Alabama, one white, the other black, must live life from the other’s eyes following a mysterious Act of God.

~ 1 ~

The stifling summer of 1965 was one spent like any other for Noah Franklin. Every morning he would awaken to bacon sizzling on the stove, and biscuits casting their tempting aroma to everyone lucky enough to be nearby. The mixture of the scents was like heaven to Noah. If only there would be enough to satisfy the craving created by the smell. There was only enough to tease the taste buds, to tickle the stomach. Ahh, but it was worth it. Noah’s mama made the best biscuits in town.

After the meager breakfast, Noah set out to do his chores. He and his younger brother, Moses, spent the day propelling an ax through mammoth logs. Over and over the ax rose and fell. They would fall into a rhythm, Noah and Moses, and sometimes they’d break into a song. They joked about heading to Detroit City and making it big in Motown.

“I’d best protect these hands. No more choppin’ wood for me! Gotta save my fingers for all them autographs I’ll be a’ signin’.” Moses sat down on a log waiting to be split and held up his hands, rotating them to observe both sides.

With a short shove, Noah had Moses sprawled on the ground, his feet sticking straight up into the air. “I’ll be sure to get you some white dainty little gloves to protect them precious little hands a’ yours. Until then, get your lazy butt back up and do some work.”

“No fun, big brother. You are no fun at all.”

Adam was the oldest of the three Franklin sons, but Noah acted the part of the first born. Noah seemed to have been born with an attitude of working to his highest ability, even when the work was as mundane as chopping wood. Noah never rested, and rarely, if at all, did he complain about anything. He refused to buy into the self-pity excuse. He accepted his lot in life and made the best of it. But being black and poor in small town northern Alabama in these racially torn times challenged his sanity daily.

Noah Franklin was seventeen years old, an age when most young men are primed for rebellion, especially in a life of extreme poverty as the Franklins were. The hours of labor had produced a body as solid as a rock. And years of living in a family of exceptional faith had made him a true child of God.

Emma and James Franklin had raised their boys with love, discipline, and an attitude of being grateful for God’s blessings. Some would not see their life in light of blessings. The family home was small, a two bedroom shack. It was surrounded by tall, skinny pine trees at the end of a long dirt and gravel road at the far and poor end of Webber, Alabama. Twenty other dilapidated houses shared the same street. They were cramped together, as if someone had thrown a handful of seed out onto the hard packed Alabama clay, and up popped the small ramshackle huts. Most of the children in this area wore the same dirty clothes day in and day out. Most went without shoes or made the old ones fit by cutting out the toes. It was a hard life, and one most would not be able to escape in their lifetime.

The two had married in 1941, when both were just nineteen. Several months later, Pearl Harbor was bombed. Raised by God-fearing parents who instilled in him a love for his country, James did his duty by joining the Army. He was sent away to fight the war and returned a decorated soldier. He was welcomed home by Emma and Adam, his newborn son. He was also welcomed home by blatant discrimination. James hoped that two years of meritorious service and risking his life for America would change the ugliness of separate bathrooms and water fountains. He was wrong.

Once a gifted baseball player, his dream was to coach the sport. A dream was all it would be because the only jobs for black men in Webber, Alabama were found at the local steel mill or odd labor jobs provided by well-to-do white people. It didn’t matter if you were a decorated soldier or a deviant. The pay was minimal. You either accepted the hard labor or moved somewhere else. If you didn’t want the work, there was somebody standing behind you in line that would. The fear of their children going hungry was enough to convince them it was the best, and only thing to do.

While James fought gallantly for God and country, Emma, pregnant with her first child, found full time work as a housekeeper for Robert and Dorothy Grace Sawyer, the richest and most powerful family in Webber. The family of Sawyers had first earned their celebrity when Robert’s great-great grandfather was a hero in the War of 1812. In every generation since that time, a Sawyer made his mark in the Alabama history books. Robert and Dorothy Grace’s son, Joshua, also came home from World War II a decorated hero. His homecoming included a small band, a parade, a large crowd, and the governor there to shake his hand. Mary Edith Chaney, well known as the prettiest girl in town, was waiting for him too. The tall brunette with milky white skin and long willowy legs had long ago caught the attention of Joshua. It was not long before the two were married and a new powerful generation of Sawyers began.

For twenty years, six days a week, Emma woke before the sun rose, took care of her own family’s needs, then walked five miles from the box she called home to the Sawyer’s Antebellum mansion. She cooked, cleaned, scrubbed, mopped, washed and dried until her fingers were numb. Then after the Sawyer’s supper dishes were cleaned and put away, Emma made the long trek back to her home. Never once did either Sawyer offer to drive her home. They believed they were doing her a favor by just letting her work. They did not owe her a thing.

Robert and Dorothy Grace treated Emma well, but with a definite air of social separation. Still, she grew quite fond of them over the years. When the older couple died tragically in an automobile accident in 1963, Joshua and Mary Edith moved into the family mansion and were kind enough to continue her employment. Joshua was now the Mayor of Webber and perhaps the most powerful Sawyer yet. Joshua was grown when Emma began working for his parents and she had rarely been around him, save for family dinners when Joshua and Mary Edith would visit.

Billy Ray Sawyer, Joshua and Mary Edith’s son, was tall, with dark hair and blue-eyes. Like Noah, his body was rock hard, but not from chopping wood and physical labor. Billy Ray didn’t have to work. His physique came from good genes and the weight room at Webber High. The girls in town thought he was gorgeous. Most of the boys wanted to be him. Emma thought he was snobbish, disrespectful, lazy, and needed a good switchin’. After two years in their employment, Emma never felt close to the family. She was a lowly paid servant. Nothing more.

On this hot August day, Emma could see her two boys chopping wood from a quarter of a mile away down the dry, dusty road. With no electricity, the family depended on a large supply of firewood to keep them warm in the winter. She paused and reflected. “Lord, thank you for giving me three fine, healthy boys. They are a mama’s dream. I don’t deserve what you give me. And I’d rather have them three sons than all the Sawyer money and that Billy good for nothin’ Ray.” Emma looked skyward. “Forgive me Lord. That wasn’t very kind." She paused and smirked. "But it’s the truth and you know it.”

From the corner of his eye, Noah spotted his mother walking toward them with a small napkin full of leftovers from the Sawyer house. He paused, set his ax upon the log he was working on and with his left hand, wiped the sweat from his brow. “Hey! There’s Mama!”

“Don’t stop on account a’ me! Hello, Moses, honey!” She said as she turned into their property. She walked up the creaking stairs, careful through habit, of stepping over the missing board on step number two. She turned and shouted to Noah. “Happy Birthday, Baby!”

“Thanks, Mama.” Noah leaped completely over the set of stairs and gave his mom a strong bear hug.

“You’re a good boy, Noah. Hoooweee! A smelly one, but a good one.” They both shared a chuckle. Noah smelled his armpits as if to test her truthfulness. He pretended to faint. “Supper’ll be ready shortly.”

Disappearing behind the screen door, the boys heard her turn on the kitchen faucet and begin singing, “How Great Thou Art.” The boys snickered quietly to themselves.

“Reckon she’s the next Diana Ross?” asked Moses.

“Yeah. And we can be the Supremes,” Noah answered. Then the two broke into a chorus of “Stop in the Name of Love” in their best female voices.

Emma peered out the window. “You boys better stick with choppin’ wood. You’ll make more money than with that slightly off key singin’ a yourn,” Emma teased.

“That ain’t true ‘cause we ain’t gettin’ a plug nickel for doin’ this,” Moses managed to say below his breath.

“I heard that, and if you keep belly achin’, I’ll find more for ya’ to do.”

Noah and Moses looked at each other and laughed. “Got the dang ears of an elephant,” Noah joked.

“I heard that, too.”

Suddenly, the front door burst open, slamming into the wall beside it and breaking the jovial mood inside and out.

“James Adam Franklin! What in tarnation is wrong with you comin’ in my house like a bunch a wild hogs. Now you go back out and open that door properly. Now!” Emma said sternly.

Adam, Emma and James’ firstborn, went back out, but stayed on the front porch. He was in no mood to test the waters with his mother. He knew from experience he would not win. His anger needed to subside before he came back inside.

“What has gotten in that boy lately?” Emma’s furrowed brow hid an even deeper fear within.

“Who you mad at today?” Noah inquired, as he leaned against the peeling paint of the front porch railing.

“Ain’t fair, Noah. It just ain’t fair.”

“What ain’t?”

“This!” Adam stretched his arms toward the house and then to their neighbor’s on all sides. “All this! Ain’t fair! What’d we do? Huh? What’d we do to deserve this?” He slapped his arms to his side. Adam was a big man, muscular from years of hard work. His hard life made him look and act older than his twenty years. Adam felt cheated out of his best years. “Look at this place, Noah. It’s falling down! Every day it rots a little more. Five of us livin’ in this God forsaken shack. Pop did his duty fightin’ the white man’s war and this is how they repay him. And me? I can’t even get a job pickin’ up their trash!”

“You didn’t get the job? Sorry, Adam.”

“This Mr. Jennings. He looked at me like I wasn’t fit to tie his shoes, but still told me they had a job. Right about then this white man come in to that office and asked about the job. The boss-man looked at me and told me the job had been filled. Told me to come back in a month or two.” Adam looked at the ground and shook his head. “I ain’t stupid, Noah. I know what they done.”

“You’ll get a job, Adam. You just gotta keep tryin’.

“You’re young and stupid, boy! You just don’t get it do you?” Adam peered deeply into Noah’s eyes. Noah couldn’t help but see the emptiness in the eyes that stared back. “We are black! We ain’t goin’ nowhere. Not me. Not you. Not Moses. Just like Pop and his daddy and his daddy before him. Face it Noah. You are poor, you’re a nigga’ and that’s all you’ll ever be worth. Nobody’s gonna give you nothin’. This is Whitey’s world! He takes everything and gives nothin’ back. Figures as long as we live out here, stay out of his way, then he’ll tolerate us, but that’s it. If we want somethin’, we gotta take it.”

“Suppa’s ready!” Emma hollered from inside the house. Her cheerful voice broke the chilling air between the two brothers for an instant, like a ray of sunshine bursting through storm clouds. Everything seemed bearable when she was around.

Noah, hurting from what Adam said, tossed one last comment Adam’s way. “It ain’t true, Adam. All that stuff you say. It ain’t true. Things are gonna change. I know they are.”

“You just keep dreamin’, brother. Just keep dreamin’". Adam poked Noah in the chest for emphasis. "But deep down you know I’m right.” The three brothers entered the kitchen. Noah made sure the door didn’t slam behind him.

“Moses, this new kitchen table is a work of art! I do believe you may have some carpentry skills just like our Savior!” Emma was being kind as the table built from plywood and some old vegetable crates pilfered from the trash of the local grocery store, looked as if it would fall apart if you looked at it the wrong way. Still, it would do. Their old kitchen table had been given to them by the kind-hearted Dorothy Grace Sawyer when they bought a new one for their home. Emma had been so proud, the table being the nicest piece of furniture she had ever owned. Unfortunately, it was reclaimed when Mary Edith Sawyer needed a table for her bridge parties. Emma was hurt, but she never let on. The table Moses built would hold a bowl of potatoes as well as any table would, Emma reasoned.

“What do I smell? What heavenly food do I smell?” James Franklin walked into the kitchen, bent over and gave his precious wife a kiss on her right cheek.

“Why, James Franklin. We were going to start without you. I thought you said you were working late.”

“Well, my darlin’. When I thought about it, I decided that working an hour or two over and makin’ a few extra dollars was not worth the thought of missin’ your meat loaf. No sir. Not in a million years.”

Emma knew it was a lie. James had been excited all week about the extra cash. Something must have happened, but she was not about to question him in front of the boys. She looked at the love of her life. He was tall, still ruggedly handsome and the kindest, gentlest man she had ever met. She was proud to be his wife.

James quickly washed his hands at the kitchen sink and grabbed a ragged towel to dry them. He sat down at the table and the family joined hands. “Dear Lord,” James began. “We are so mighty grateful for all you have given us this day. Continue to bless my dear wife whose loving hands prepared this meal. Bless our three sons who bring us joy every day. And on this very special day, bless Noah, who on this day seventeen years ago, entered our lives. Be with him all the days of his life. Bless this food to nourish our bodies. In your Son’s Holy Name we pray. Amen.”

“Amen,” the rest of the family said in unison.

“And now, I do believe someone has a gift somewhere,” Emma said, reaching for something hidden under her chair.

“Now, Mama, don’t. I know we can’t...”

“You hush up young Noah and be thankful for what you get. Now you open this up, ya’ hear. I’ve been about to bust to give it to ya’.”

Noah took the small box with the string ribbon and shook it by his ear. “I think it’s a new car! How’d you get it in this tiny box?” Grabbing one end of the string, he tugged until it was off. Then he slowly opened the present, pulling out a small object wrapped in white tissue paper. When the paper was pulled away, a small, shiny silver cross lay in the palm of his hand. His name, in all capital letters, was engraved into it. He stared silently for a minute. “Wow. I couldn’t have asked for a better gift. Thanks Momma, Pop.” He slipped the cross into his tattered overall pocket. “I’ll keep it in my pocket always.”

“And when you need the good Lord’s help, pull it out and look at it then squeeze it tight. It will be there to remind you there ain’t nothin’ you can’t face that God can’t help you through. That’s the truth, son,” James offered.

“Okay, okay. Great gift. Can we eat?” Adam sighed impatiently.

Emma shot her eldest a half serious frown and then began passing the bowls of food. Judging by the clinks and scrapes of utensils on the ceramic bowls, and the ensuing silence, she knew this dinner would be history in a matter of minutes. She smiled for a moment and counted her blessings.

After dinner, Emma walked to the kitchen cabinet with something wrapped in a napkin. “Wouldn’t be a birthday without birthday cake. Or tea cakes at least!” She ceremoniously unwrapped two tea cakes she had made for the Sawyers, but had been too brown for Mrs. Sawyer’s taste. She gave a whole one to Noah, the birthday boy, and split the other one between Adam and Moses. The boys gobbled them up in a minute and she was afraid they would lick the crumbs off the table.

“Moses, see what we got in the mail, today, will ya?” James asked as he leaned back in his chair. Moses gathered the few pieces of mail from the table by the door. He thumbed through them.

“Pop, this letter is from the Webber School Board. Wonder what they want?”

“Open it up Pop.” Noah sat on the arm of the chair next to James. He was as curious as the rest of them as to the letter’s content.

“Let’s see,” James began, holding the letter out at arm’s length. “Well, I’ll be. I don’t know what to make of this. I just don’t know.”

“What Pop? What’s it say?” Moses couldn’t stand the suspense.

Noah was already reading the letter over his father’s shoulder. “They’re integratin’. The high school anyway. I’m gonna have to go to Webber High.”

James read, “This is to advise you that effective September 8, 1965, all children entering grades ten thorough twelve in Webber will be required to report to Webber High School, and so on and so forth. It says down at the bottom they’ll send a bus to pick you up down at the crossroads.”

Moses, entering the ninth grade would not be affected. “Does this mean that Noah’s going to a school with white folks?” He shook his head. “Don’t think I’d like that very much. Un-uh, wouldn’t like that at all.”

Noah grinned. “I’ll be fine, Moses. White folks is just like us. Just a different color. That’s all.” Deep inside though, there was a sick feeling in his belly.

“You think the white teachers’ gonna be fair to the colored kids?