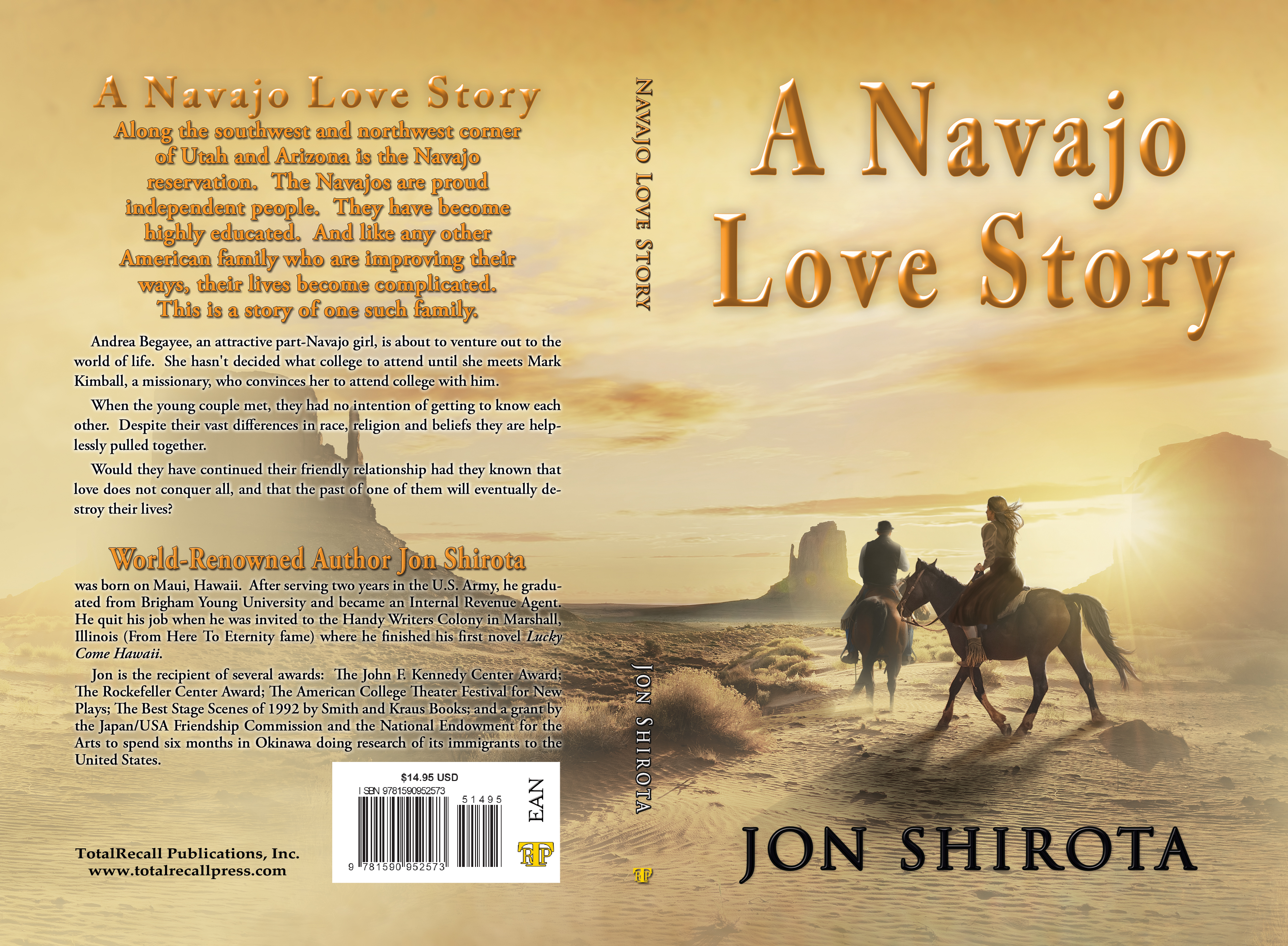

A Navajo Love Story

Jon Shirota

Jon Hiroshi Shirota. Born and raised on MAUI, HAWAII. After two years in the U.S. Army graduated from Brigham Young University, in Utah. Worked as an Internal Revenue Agent for seven years before joining the Handy Writers Colony in Southern Illinois where he finished his first novel, LUCKY COME HAWAII. I would like to dedicate this novel to my wife, BARBARA SHIROTA. (As mentioned to Corby, I'd like to publish the following endorsements): 1. Professor George Hendrick, emeritus, writer, author, at University of Illinois; 2. Ray Elliott, Marine, writer, former president of James Jones Literary Society; Ed. Sakamoto, playwright, author, reciepient of Pookele Award, Hawaii's most prestigious award for excellence in writing; and Professor Katsunori Yamazato, author, lecturer, President of Meio University. Special thanks to Professor Marie Yamazato for her devoted editing and translations throughout the writing of this novel.

Jon Shirota was born on Maui, Hawaii. After serving two years in the U.S. Army, he graduated from Brigham Young University and became an Internal Revenue Agent. He quit his job when he was invited to the Handy Writers Colony in Marshall, Illinois (From Here To Eternity fame) where he finished his first novel Lucky Come Hawaii.

Jon is the recipient of several awards: The John F. Kennedy Center Award; The Rockefeller Center Award; The American College Theater Festival for New Plays; The Best Stage Scenes of 1992 by Smith and Kraus Books; and a grant by the Japan/USA Friendship Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Andrea Begayee, an attractive part-Navajo girl, is about to venture out to the world of life. She hasn't decided what college to attend until she meets Mark Kimball, a missionary, who convinces her to attend college with him.

When the young couple met, they had no intention of getting to know each other. Despite their vast differences in race, religion and beliefs they are helplessly pulled together.

Would they have continued their friendly relationship had they known that love does not conquer all, and that the past of one of them will eventually destroy their lives?

Andrea Begayee, an attractive part-Navajo girl, is about to venture out to the world of life. She hasn't decided what college to attend until she meets Mark Kimball, a missionary, who convinces her to attend college with him.

When the young couple met, they had no intention of getting to know each other. Despite their vast differences in race, religion and beliefs they are helplessly pulled together.

Would they have continued their friendly relationship had they known that love does not conquer all, and that the past of one of them will eventually destroy their lives?

In Fond Memories Of Ramona

Navajo;Love;romance;Mormon;missionary;Jon Shirota;college life

33000

Along the southwest and northwest corner of Utah and Arizona is the Navajo reservation. The Navajos are proud independent people. They have become highly educated.

CHAPTER 1

The golden sun to my back was sinking beyond the southwestern rim of the Grand Canyon when I braked the brand new ’69 Ford pickup beside the two sandy-haired whites walking along the highway. “Want a lift?”

The slender one quickly opened the door and stepped in out of the chilly, early-spring wind. “Thanks a lot,” he smiled gratefully.

I waited for his heavy-set companion to get in. “Where are you going?”

“Rainbow City.” The slender one slid closer to let his companion shut the door. “Is that where you’re going?”

Nodding, I shifted into gear and picked up speed.

“I’m Mark Kimball,” said the slender one. “This is Dale Wilkens. We’re Mormon missionaries.”

I knew who they were when I stopped. Dark-suited Mormon missionaries were always walking along the reservation highways, never thumbing for rides but accepting them when offered.

Mark kept looking at me. “It was getting pretty cold out there,” he said, blowing into his hands, rubbing them vigorously. “We’re on our way back from Cameron. Is that where you’re coming from?”

I shook my head.

“From Flagstaff?” Dale asked.

I shook my head again. I had herded sheep all day with my grandmother in Melon Canyon north of Cameron, and was quite tired. I hoped the missionaries wouldn’t attempt a polite conversation.

I kept driving silently through the narrow, winding road towered on both sides by crimson crags and cathedral spires, wondering what Grandma was doing alone in her Hogan. I had wanted to stay with her, but she had insisted that I return home with the fresh pot of lamb stew she had prepared.

“You wouldn’t by any chance be a member of our church?” said Mark, hopefully.

“I’m a Presbyterian.”

“Oh. A Presbyterian?”

That should stop him. Actually, I did not belong to any church. But a Navajo not belonging to one the churches in the reservation was a potential convert. And jees! There were as many preachers as church goers.

Rainbow City alone had ten different churches. Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-Day Adventist, Church of the Brethren, Quaker, Catholic, Christian Reformed Church, Mormon, Massonites and the Plymouth Bretheren Church. Oh, yes, the Navajo Bible Academy.

Eleven!

They were all run by zealous, well-meaning whites, determined to save us pagans from damnation. Some of the God-fearing converts belonged to as many as half-dozen churches.

Although my mother, a half-white, was raised as a Catholic, I grew up with the spiritual beliefs of my paternal grandmother. I learned about the great history of our people from her and about the grim suffering they endured when the Spaniards and later, the Belliganos invaded our land. I also learned about our ceremonial “sing,” our chants and our sand painting rituals from her. I was brought up to believe that our people were protected by the four sacred mountains surrounding our land: Big Sheep Peak on the north. Mt. Taylor on the south, San Francisco Peaks on the west and the Pelado Mountains on the east.

“I know who you are!” Dale suddenly snapped his fingers. “You’re Andrea Begayee, last year’s rodeo queen for the Rainbow City fair. Right?”

I felt myself blushing. I looked everything but a queen at the moment, my face dirty, my long black hair disheveled, my patched jeans and grubby sweater reeking sheep and horse dung.

Mark stared at me, but said nothing.

“I thought you looked familiar,” said Dale. “Your picture was in the Navajo Times.”

In the white papers, too, I was tempted to tell him.

“You’re a bronco rider, right?” said Dale.

The papers had exaggerated it, but I nodded pridefully.

“Ever get hurt riding one of those horses?” Dale asked.

“Naw…” I shrugged. If he did not know that I had given up bronco riding after breaking my arm in the fair rodeo I wasn’t about to tell him.

“There must be quite a few Begayees in Rainbow City, too,” Mark now said.

I nodded. “Begayees is as common as Smith and Jones.”

“Yes, I know,” he said.

“Going on to college after high school?” Dale asked.

“NAU,” I said. “On a scholarship.” He apparently did not know what NAU stood for. “Northern Arizona University,” I said.

“Oh, yeah. NAU. Good school. On an academic scholarship?”

I nodded pridefully.

Another round of silence. I thought it was my turn to be polite.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

“Salt Lake City,” Mark replied. “Dale’s from Las Vegas. We finished a year at the Y before coming on our mission.”

“The Y a high school in Utah?” I asked.

“The Y?” Mark laughed. “Brigham Young University. Ever heard of it?”

“Of course,” I said. Why didn’t he say so in the first place?

“What are you planning on majoring in?” Mark wanted to know.

“Education.”

“And teach here in the reservation?”

“In one of the high schools,” I said. “It won’t be long before all the teachers in the reservation will be Navajos.”

“That would be great,” he said.

I looked at him. Was he sincere? Or was he like the rest of them who thought Indians were stupid and incapable of learning?

“How long have you been in the reservation?” I asked.

“A year,” he said. “We spent most of the time in Holbrook. We’ll be in this Area for the rest of our mission.”

“How long is that?”

“Another year.”

Then go home and tell your people what a great guy you are for spreading the good word among us poor Indians.

At last after driving through miles of barren flatlands with dwarf pines and sage brushes dotting the hillsides, I rounded the long bend and came to the Rainbow City intersection where the town’s main service station and trading post were. It was windy and the tall trees at the church and school grounds had turned a dull gray from the powdery dusts.

“Are you going back to your church?” I asked.

“It’s just down the road,” said Mark. “We’ll get off at the corner.”

“I’m going that way,” I said.

Honking my horn, I waved to Johnny at the station and made a sharp right. Johnny looked up from under the hood of a car he was servicing and waved back.

“Your boyfriend?” Mark asked.

“My brother,” I said. “He and my father run that station.”

“They do any mechanical work?” Dale asked. “Our car’s broken down.”

“My father is the best mechanic in town,” I boasted. I wasn’t going to tell him that Dad was the only mechanic in town.

“You don’t have to take us all the way down,” Mark said.

I had already turned into the dirt road toward the church, a L-shaped white building with a steeple. Their home, a house trailer, was behind the church. Closeby was a fenced-in graveyard.

Dale thanked me when he got off.

Mark slid over to the door and looked at me, his greenish-brown eyes smiling warmly. “Well,” he said, “thanks again.”

He stepped out and held the door open. “If you’re not doing anything tonight, why don’t you drop by? We’re having a show, then later dancing.”

“I’m going to be busy,” I told him. “Thanks anyway.”

He shut the door, stood there, and waved.

I swung the pickup around, climbed back up the dirt road and looked into the rearview mirror. He was still standing there. I crossed the highway into the driveway of our home above the church and glanced back. He was rounding the church, looking toward me.

CHAPTER 2

The next time I saw him was two weeks later at our fairground corral.

He had become a hero among the young Mormons in Rainbow City. He had defeated Ray Eagleton, our finalist in the state wrestling championship, and had held my brother, Johnny, to a draw in a boxing match at the gym. Now, he was going to show us what big-time bronco-riding was like.

It was a Saturday afternoon and all of the kids from town were there at the corral on the hillside. I had gone there to tell Johnny that a customer was waiting to have his car serviced. Johnny had gotten out of the Army only three months before and, still restless, spent most of his time at the gym or the corral breaking wild horses. Having been decorated in Vietnam and winning the Division middleweight boxing championship, he thought he should be doing more important things than servicing car.

I joined the others on the fence and waited for Johnny to bring in the horse. It was a big roan. The same one Johnny was having difficulty breaking. Following closeby was Mark. Unlike Johnny who had on riding boots, Levi’s and work shirt, he was wearing a pair of loose, light-brown slacks, sneakers and a BYU sweater. As his followers cheered him on, he smiled and waved to them.

I called Johnny. He handed the reins to his friend, Pancho, and came over.

“What?” he said, adjusting the headband that held down his long, shoulder-length hair.

“Dad wants you to change the oil in Mr. Johnson’s car.”

“Aw…” he grumbled. “Let him wait.”

“Johnny!”

“I’ll be over in a few minutes. I wanna see if that white is as good as he thinks he is.”

“Dad’s waiting.”

“Tell him you couldn’t find me,” he said swaggering off.

I wasn’t about to return to the service station without him.

Johnny was still bitter over his experience in Vietnam. As always, the whites had to prove their superiority over the non-whites, he said. They massacred the Vietnamese like they did the Indians.

That, of course, was not the only reason he was bitter against the whites and mistrusted them. A few months after he was drafted, our brother Billy, a year younger than Johnny, had volunteered in the Marines and had gone to Salt Lake City to say goodbye to his girlfriend who had just moved there. The following day, we received a call from the Salt Lake City Police Department. They said that Billy was killed in an accident. We could not believe it! Dad rushed up to Salt Lake City and was told that Billy had been drunk and was crossing against the street light when a car struck him. The police would not give Dad any more information. Not even the driver’s name. They said that it was an “open and shut” case. If Dad wanted more information he would have to hire an attorney.

Johnny returned home on an emergency leave to attend Billy’s funeral. He was angry with Dad for not finding out what had really happened. He wanted to drive up to Salt Lake City, but was due back in camp.

He still could not believe that Billy was gone. Not even after the funeral. Johnny, who had been very close to Billy, was terribly bitter over the accident. He said that Billy drank a beer or two occasionally, but was not the type to get drunk. What about the driver? he questioned. Did they check to see if he was drunk? Why didn’t they at least give his name?

Johnny had vowed that he would get to the bottom of it when returned home from the Army. A few days after his discharge, he drove up to Salt Lake City, determined to know the truth. They not only gave him the same treatment they gave Dad; they said that the accident had happened over two years ago and the records show that Billy was struck by a car while crossing against the street light. They would not give Johnny any more information. When he protested again, they threatened to arrest him for causing a disturbance.

Returning home, Johnny was even more convinced that the driver was someone very influential. He vowed that if it took him the rest of his life, he would find out exactly how Billy was killed and who did it.

The roan was fractious, his dark, fiery eyes darting here and there. Johnny led him to the center and, handing the reins to Mark, held the roan’s head and waited for Mark to mount. The roan shied away spiritedly. Johnny held his head tighter and moved along with him until he settled down.

Mark lifted his foot into the stirrup and got up confidently.

“You ready!” Johnny called out.

Mark adjusted the reins and sat firmly in the saddle.

“Ready!”

Johnny let go of the rein’s head. The roan squealed and snorted bucking wildly.

Mark went high in the air and was thrown hard on the ground.

The crowd gasped as he lay breathlessly. Then, applauded and cheered when he gathered himself up.

“You can to it, Elder Kimble!” they encouraged. “You can do it!”

Johnny and Pancho chased the roan into a corner.

Catching his breath, Mark wiped the dirt of his slacks and sweater, and staggered toward the fence I was sitting, his eyes glassy.

“You’ll right?” I asked, as he leaned against the fence.

“Yeah…” he said, shaking his head, pressing his side. “Yeah, I’m all right…” Then, recognizing me, “Oh, hi…”

“Don’t tell me you’re going to ride him again.”

“Can’t do worse than I just did,” he said, grinning that boyish grin of his.

“Are you sure you’re a bronco rider?”

“I’ve ridden horses before,” he said.

“Wild ones like that roan?”

“Oh,” he said, “is that what it is?”

“What did you thinks it was? A jackass?”

“Hey!” Johnny called. “You gonna try again or not?”

I jumped of the fence and stormed over to Johnny. “You trying to get him killed!”

“He’s a bronco-riding champion, ain’t he?” Johnny grinned.

“He’s not more a bronco rider than you’re an astronaut,” I said. “Can’t you see he’s doing it just so he wouldn’t let the kids down.”

Mark came over.

“You’re going to ride him!” I said.

“Why not?” He took the reins from Johnny. “It can only kill me.”

Johnny shrugged.

“Look,” I said. “You want to break your neck it’s your business. At least give yourself a chance. Hold the reins tighter and try to ride with the bucking and pitching. Don’t fight the rhythm.”

He stuck his foot into the stirrup, grasped the saddle and jumped on.

Johnny let go the roan’s head and hopped on the fence beside me. “That crazy white,” he said, grinning, “he’s got more guts than the whole bunch of ‘em I knew back in Nam.”

That was about the highest compliment I had ever heard Johnny give a white.

Snubbing the reins now, Mark rode the vicious bucking and pitching a second or two longer than before. Just as he was thrown, he kicked the stirrups off and managed to land on his hands and knees.

The roan raced around the corral until Pancho cornered it.

Mark came over unsteadily. “I’m learning to fall better, that’s for sure.”

Learning to fall better. Jees! Don’t missionaries ever swear? If that had been Johnny he’d be cursing all over the place.

“Wanna try again?” Johnny asked.

“I’m willing if that creature is,” Mark said, determined.

“Naw,” Johnny relented. “You’ve had enough.

Mark glanced toward his followers. “Well,” he said gloomily, “they had a good show anyway.”

“Hey,” said Johnny, “why’d you tell them you’re a bronco rider?”

“Me?” Mark said. “Me a bronco rider?”

“That’s what the kids in your church went around saying.”

“Oh…” Mark nodded, grinning to himself. “That’s what it’s all about.”

“A big-time bronco rider, that’s what you’re supposed to be,” said Johnny.

Mark laughed. “When one of the kids asked if I could ride a wild horse I told him I used to go to the Nevada deserts and lasso mustangs.”

“Lasso mustangs!”

“So help me. That’s all I told him.” Mark glanced over toward his followers. “I let them down, huh?”

“Aw, hell,” said Johnny. “You did okay.”

“For a mustang lassoer,” I said.

“Hey, Pancho!” Johnny called. “Bring him here.”

“You’re going to let him ride again!” I protested.

“Naw. Not him,” said Johnny. “It’s my turn this time.”

As Pancho held the roan’s neck and Johnny prepared to mount, the crowd broke into a loud applause.

“Atta boy, Johnny! Show him! Ride ‘em to a standstill!”

Johnny stuck his feet into the stirrups, kicked them off, something I had never seen him do before.

“Ride ‘em, Johnny! Ride ‘im!”

The roan lunged, kicked and zigzagged viciously. Another jolting buck and Johnny lost his leverage. He went flying into the air, but managed to land unhurt on the ground.

The crowd was disappointed. The missionary had been on longer.

Getting up, Johnny dusted himself, shaking his head. He gave the crowd a harsh look. “Anyone else wanna try!”

No one volunteered.

“C’mon!” he challenged. “Nothing to it. Just ride it to a standstill.”

Everyone remained silent.

“You don’t have to try twice like the missionary did. Just once!”

Silence.

“No guts, eh?” He swaggered toward the roan.