Coon Dogs and Outhouses Vol 1

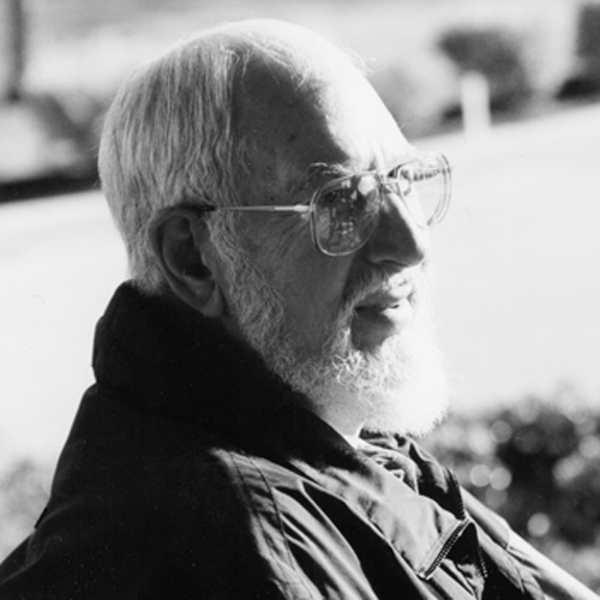

Lucas Boyd

Dr. Lucas G. “Luke” Boyd was born in a three-room shotgun house on Jabe Dunaway’s place near Anguilla, Mississippi in the depths of the Depression. His father managed one of those sprawling cotton plantations the Delta was known for, and it is this plantation culture that left an indelible mark on young Luke.

After a stint in the Army and then earning a Ph.D. in English History at the University of Tennessee, he began a career in education that spanned 48 years both at the secondary and college levels. He retired after serving for 19 years as Principal of Battle Ground Academy, a private college preparatory school in Franklin, Tennessee.

“Sometimes I stop and try to figure out where the stories come from and why I write the way I do. I’m sure much of it is a result of the land I grew up on and the people who were trying to scratch a living from it. If he stays in contact with it long enough, the land will brand a man as surely as the red-hot iron brands a Western calf. I’m sure the flat, almost treeless, bayou studded Delta of my early years, which later was replaced by Mississippi’s rolling, red clay hills, both left their marks on me….My father was a good storyteller and I suppose I picked up some of his talents. There is much satisfaction in telling a good story…”

Luke Boyd’s first collection of 25 short stories reflects the folk humor and local color that are hallmarks of Southern writing. His story telling is part remembrance of a culture that is gradually fading, part recollection of lessons learned over a lifetime. His matter- of-fact style and clarity of detail are cut from the cloth of the oral tradition that flourished in the rural South of his upbringing. He deftly places the hilarious story of chain saw-toting Phinos Ledbetter and his botched baptism at the East Fork Southern Missionary Baptist Church alongside the powerful memory of an uncle known by the poor tenant farmhands he served only as “The Jesus Doctor.”

These unforgettable characters are depicted so clearly and accurately as to leave the reader guessing which stories are fact and which are imagined. And whether the teachers in these tales are smudged with the dust of chalk or caked with the mud of the field, their lives and lessons are faithfully recorded here in straightforward prose that evokes a special time and place.

For Sara My wife of over fifty-three years, For her love, help, faith, and encouragement

folk, tales, south, tall,

Ol’ Raymond

He was the first dog I ever knew. The first memories I have of anything or anybody--the house, the yard, my parents--include him. He was as much a part of my family and my early existence as were my parents and younger brother and I loved him greatly.

His name was really just Raymond. I never knew why we tacked the first part on. He surely was not old. I suppose it was a title of affection or endearment.

Ol' Raymond was a red-bone coon hound and a credit to his breed. He was a big dog. I'm sure he seemed big to me because I was so small. But the pictures verify his size. Judging from the size of Gene, my brother, I was somewhere between three and four years old. In one, I am standing at his shoulder and Gene sits astride him like he's riding a horse. The dog and I are about the same height. In another, he carries both of us on his back with ease. As I said, he was a big dog.

He was an outside dog. In that time and place, no one kept a dog in the house. He generally slept on one of the porches in warm weather. In the winter, he would scratch himself out a depression under the house on the south side of the chimney base and use the warm bricks for heat.

Ol' Raymond was a very protective dog. As I roamed about the farm, I knew that I had nothing to fear from anything or anybody as long as he was with me. In fact, he was the protector of the whole family. My daddy was sharecropping a new-ground farm in the western part of the Delta toward the River. After crops were laid by and during the winter, he was away from home a lot doing carpentry work. We had an unpainted picket fence around the yard and I heard my mama say on more than one occasion, "No, we're not afraid to be here by ourselves. Ol' Raymond won't let anyone inside that fence when Luke's gone." Ironically it was this protectiveness that would prove to be his undoing.

My daddy hunted a lot to put meat on the table. He also ran a trap line trapping mostly mink and raccoon for their pelts. I'm sure the skins didn't bring much by today's standards, but in the mid '30s, any extra income was a bonus. There were usually several skins drying on stretcher boards out by the smokehouse.

He also went coon hunting at night with other men who had coon dogs. They would always come back with coons, but this type hunting was mostly for sport. This was where Ol' Raymond really proved his mettle. Men would come from miles around to run their dogs with him, and I never tired of hearing the stories my daddy told about his prowess in the hunt. My favorite was his confrontation with Pegleg.

Pegleg was a big boar coon who ranged around the nearby bayous. He'd been trailed but never treed, seen but never caught. He got his name because of a missing paw. That leg ended in a stump which left a very distinctive track in the soft, swampy ground. My daddy theorized that the missing paw was chewed off by the coon himself when he got caught in a trap and could free himself no other way. Coons were known to do that.

Anyway, by this time Pegleg was old and grizzled and smart. He knew how to avoid traps and he also knew any number of ways to throw off a pack of dogs who were hot on his trail. Sometimes he would backtrack on his trail and go off in another direction through the trees leaving no scent on the ground. Or he would swim down a creek or crisscross a creek several times to cause the dogs to lose his trail in the water. As a result, Pegleg had never been treed.

One night the men turned the dogs loose and they struck a hot trail immediately. They ran almost in a circle and soon their trailing bark changed to one that told the men that they had their quarry at bay very close by. The hunters hurried toward the sound and came to the bank of a large bayou. The coon's tracks showed the missing paw. It was Pegleg. Only he wasn't up a tree. He was too smart for that. The dogs had apparently picked up his trail very close to him and pushed him so hard that he had no opportunity to use any of his tricks. But the old coon wasn't giving up by any means. The light from the carbide headlamps reflected off his eyes as he sat on a log out in deep water waiting. The other dogs stood on the bank barking. Ol' Raymond was swimming out to get the coon.

Now, the last place a dog wants to confront a coon is in water. A coon will usually wrap himself around the dog's head, forcing it under the water while keeping his own above the surface. In a very few minutes a big coon could drown a dog or whip him so badly that he would leave the fray.

Of course, my daddy had a gun and could have shot the coon, but the dog had brought him to bay and the sporting thing was to allow the dog to try to finish the job even if he got killed in the process.

But Ol' Raymond had fought coons in water before and come out the winner. Instead of trying to hold his head up when the coon climbed aboard, he would do the opposite and push the coon under water, causing him to release his hold to get to the surface. After two or three repetitions of this, Ol' Raymond would get the coon worn down and get his jaws on the coon's neck, ending the fight. But this was not just any coon.

Sure enough, when Ol' Raymond got to the log, Pegleg attacked. He jumped on the dog's head and began biting him about the ears and neck. Ol' Raymond rolled him under and broke the hold. They surfaced and the process was repeated and then repeated again, and again, and again, until my daddy lost count. He confessed that at that point he was wishing he'd shot the coon, but it was too late for that. The two combatants were throwing up so much spray and foam from the murky water and were so closely intertwined that a shot would just as likely hit the dog as the coon. The fight was both furious and long--longer than any fight like this these men had ever seen. Suddenly, the coon let out a squeal that told them that Ol' Raymond had the coon in his jaws and the fight was over. He tried to drag Pegleg to the bank but was so exhausted that the men had to wade out and help him. The men vowed that they had never seen such a fight in all their years of coon hunting and Ol’ Raymond's fame spread even farther. The tear in his ear and the cuts on his face and head would heal and be worn as proudly as a dueling scar--the marks of a coon dog who had fought and won.

It Happened on a Saturday

I know it was a Saturday because we had been to town. We never went to town any other day because there was too much work to do to waste time going to town during the week. My daddy would usually work until noon on Saturday. After we ate, Mama would get the number three washtubs down from their nails and fix bath water for all of us and we'd get our only full bath of the week. Then, we would all pile into our Model T Ford and head for the bright lights of Rolling Fork, a town with a population of about eight hundred. My parents would purchase whatever staples we needed at the grocery store where, if I were good, I'd get to have a cold Orange Crush from the ice-water filled drink box. Most of the rest of the time would be spent sitting in the car watching people pass by on the town's main street. We couldn't stay late since we had to get home to do the milking and other chores before dark.

On this particular Saturday when the Model T rolled to a noisy stop beside the house, something was amiss. Ol' Raymond did not come to the side gate to greet us. "Where's Ol' Raymond?" I asked.

"He's probably run off chasing a rabbit or squirrel," Mama responded.

"Naw," my daddy replied, "he wouldn't leave the house with no one here." As he got out of the car, he added, "There he is lying up there on the porch."

"Is he just asleep and didn't hear the car?"

"He had to hear the car. He's laying funny."

"Do you reckon he's sick? Do you think something's wrong with him?"

"I don't know. Let me go see," said Daddy as he moved toward the house.

We stood by the car and watched him walk up on the porch and squat beside the dog. He felt around on him, moved his legs, and examined him carefully around his head. The dog hadn't moved. Daddy stood up and came slowly back to the car. He had a look on his face I'd never seen before. "He's dead. Somebody poisoned him."

Mama began to cry. Gene was too young to understand what had happened. I didn't really understand either. I had heard about death, but I really didn't comprehend what it meant. In my short life, no person or animal I had any connection to had died. I just knew that the feeling I was feeling inside was not good.

Daddy went back up on the porch, gently picked Ol' Raymond up in his arms and carried him around to the back of the house. When he came back, we were still standing by the car. "The chores have to be done," he said.

Mama went to milk and Daddy went to tend the livestock. Gene and I sat on the front porch. I kept wanting to see Ol' Raymond come bounding around the house and up on the porch to greet me as he always did with his tail wagging as he administered wet licks to my face and hands. But it didn't happen. I thought if I closed my eyes and wished hard enough, Ol' Raymond would come. I tried. I tried real hard, but the only thing that came was the darkness.

Why would somebody poison a person's dog? I've thought of that often since that day. Mama said it was just pure meanness. Daddy said that some people are always wanting to steal something and they just don't like good watchdogs in general and they try to get rid of as many of them as they can. We surely didn't have anything worth stealing. The most valuable thing we had was the meat in the smokehouse. Whoever did it knew we weren't home, so he just walked by, threw a piece of poison-laced meat into the yard, and kept on going. When Ol' Raymond knew something was wrong, he came to the front door for help, but there was nobody there to help him. Some lowdown human had done what the toughest coon in the swamp couldn't do.

After supper Daddy got up from the table and said, "We'll have to bury him." He got a lantern and lit it and we all followed him out back. He stopped at the tool shed for a shovel and continued down the path that led to the field. When he located a suitable place near the corner of the backyard fence, he sat the lantern down and began to dig. The black buck-shot soil offered little resistance to the shovel and Daddy soon had the grave dug. Then, we all went up to one of the outbuildings where Daddy had put him. On the way back, Mama led the way with the lantern; Daddy came next carrying Ol' Raymond; Gene and I stumbled along behind.

As Daddy was about to lay Ol' Raymond's stiffening body in the grave, Mama said, "Luke, we just can't put him in the cold ground. Let me go get something." She took the lantern and hurried back to the house returning shortly with an armload of newspapers. She got down on her knees and lined the grave with them. Daddy put him in and we all said goodbye. Mama covered him up with newspapers, tucking them in good so the dirt wouldn't get on him. Then, we stood and watched as Daddy shoveled in the dirt.

As I stood there, I had a hurt somewhere down deep inside me that made me hurt all over. And the tears rolling down my cheeks didn't help any. And that hurting stayed with me for a long time. I've experienced the deaths of my parents, grandparents, and numerous friends, but I don't think my feeling of grief has ever been any greater than it was the night we put Ol' Raymond in the ground.

Even as this was happening, I could not accept the fact that Ol' Raymond was gone for good. I had seen Daddy plant things in the garden and corn and cotton in the big fields. Not long after the planting, green shoots would be pushing up through the ground. Why would this not be the same?

As Daddy was rounding off the dirt on the grave, I asked, "Daddy, will Ol' Raymond come up?"

He stopped and leaned on the shovel for a few seconds before he answered, "No, son, he won't." But I persisted, "Daddy, I think he'll come up."

"No, son, I'm sure he won't."

But I would not accept that answer. I was sure Ol' Raymond was going to come up out of that ground just like a stalk of corn did. For a long time, I went to his grave everyday and looked for a paw or his nose. No matter what anyone said, I just knew it would happen. In fact, I can remember two or three times going to my mother and saying, "I just passed Ol' Raymond's grave and I saw his nose sticking out. He's coming up, Mama." But each time I was told that it was just my imagination which, indeed, it was. Eventually, I had to accept as true what my parents were telling me. Death was final. I would never see him again.

Ol' Raymond deserved better. He was a credit to his breed. He was faithful and brave. He helped his master in the hunt and he protected his family when he was gone. He didn't deserve to be done in by a coward with some poison in a hunk of hog meat. It would have been better for him to have been bested by some tough old boar coon out in a bayou amongst the cypress knees and water snakes. That would have been a noble end for a noble dog.

Daddy’s Stories

Introduction

My father loved to tell stories and tall tales. Some were true. Others had some elements of truth in them--maybe just enough to make the listener think they could be true, at least until toward the end of the tale. He had a way of making an observation or turning a phrase that would catch your attention and make it easy to remember. I recall one such phase at one of our Fourth of July fish fries.

Our little country community where I spent my junior high and high school years got together every year for a big fish fry on July 4. There weren’t any public parks close enough to go to. Someone would scout around and find a place on the bank of the river or the shore of a nearby lake. Some would come early in the morning, eight or nine o’clock, bringing pickup loads of rough lumber. They would set to building a long serving table and benches all out among the trees. The fire pit would be dug and firewood gathered. A support for the big black wash pot in which catfish and hush puppies would be fried would be constructed. Later in the morning others would come bringing all sorts of vegetable dishes, salads, and desserts to round out the meal.

We were usually the only ones around, but this particular year we had selected the shore of a horseshoe lake near the Tallahatchie River, and another group had come in about fifty yards up the shoreline. Only they were not having a fish fry. The first thing they set up was a very large, black pot. I'd never seen one so big. It must have been five feet across and was so heavy it took several men to get it into position. They filled it about half full of water and started a big fire under it. Then, they began to put all manner of things in the pot. It seemed like everybody added something different. There were whole onions, potatoes, tomatoes, okra, and a number of vegetables we could not identify. The meats were equally varied. We could agree that there were pieces of pork and beef, whole squirrels, rabbits, and quail, and several other things we couldn't name. I had been sitting around with a group of the men who were watching this operation and making comments about this communal stew being created before our very eyes. A late arrival joined our group and observed the activity for a few minutes before asking, "What in the world have they got in that pot?" My daddy replied, "Well, D. J., the best I can figure out, they've got everything in there from bull nuts to cooter."

(Cooter was a local term for a turtle.)

Since these are my daddy's stories, I'm going to try to write 'em like he told 'em.

The Kicking Gun

One day early last fall, before the cotton was ready to pick, a bunch of us were down at the store sittin' around on the porch visitin' when ol' Bill Butler drove up. The conversation got around to guns and huntin'. Bill told us about what happened to him a coupla weeks before.

Said he had gone to town to get a piece for one of his wagons and had stopped by the feed store. There were eight or ten fellows, some he knew and some he didn't, sittin' under the shed. They were talkin' and swappin' knives when one fellow Bill didn't know started tellin' them about a shotgun he had. Said it was the hardest kickin' gun he'd ever shot. Some got to askin' about it, so he went and got it out of his truck.

Everybody looked at it. It was a Remington pump and it wasn't very old. Said he wouldn't mind tradin' it off. At that, Bill went out to his truck and got his gun and let the fellow look at it. Bill's was a pump, but it was an older model Stevens. The Remington was much better and newer, but Bill could really shoot his old Stevens and wasn't too hot to trade. At least that's what he kept saying. But that fellow was in a tradin' mood, so he offered to throw in an almost new Barlow knife to boot. Bill thought he had himself a mighty good deal, so he agreed and they swapped right there.

Now, the fellow had warned Bill that the gun would kick, but Bill said he'd been shootin' all kinds of guns for thirty years and figured there wasn't a gun around that could get the best of him. Well, he was wrong. Said he'd been out with it three or four times and the gun had about kicked him to death no matter what he did. Said the last time out he'd missed several easy shots because he was gettin' afraid of how hard the gun was gonna kick him.

At that point I started kiddin' him about not bein' much of a man and not knowin' how to shoot, to let a little ol' gun get the best of him. Well, that kinda got away with him and he said, "All right, Luke, you think you're such a hotshot shooter, you just take this gun out and see if I'm not tellin' the truth. I'll even give you a handful of shells so you won't have to use up any of yours.” With that, he went to his truck, got the gun and put in my truck.