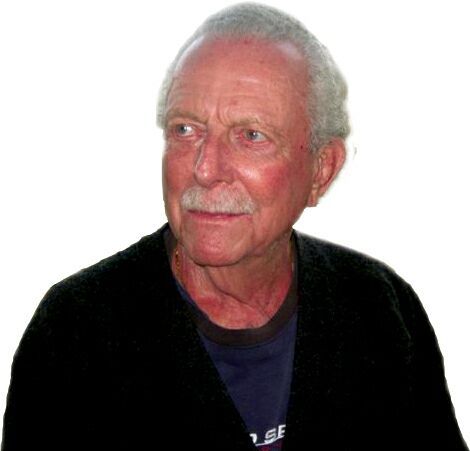

Jerry Yellin was a P-51 pilot in WWII who flew nineteen missions over Japan. Jerry and his wife of sixty-one years, Helene, have four sons and six grandchildren—three living in America and three in Japan. Jerry is a member of the Military Writers Society of America; author of three award-winning books, Of War and Weddings, The Blackened Canteen, and The Letter; and an honorary board member of the Iwo Jima Association of America.

http://www.JerryYellin.com

jerry@lisco.com

It has been said that the only warriors who do not suffer after being in combat are those who were killed. I cannot attest to that for all battle-tested warriors, but I certainly can for one—me.

It has been said that the only warriors who do not suffer after combat are those who were killed. I cannot attest to that for all battle tested warriors but I certainly can for one---me. Some years ago a young, 13 year old eighth grade student from the Fairfield, Iowa Middle School once asked me, "Were you wounded in the war?

I had been invited to speak in Mrs. Broz's class for many years to talk about my wartime experiences. I had been asked and answered many questions but this one was different. I paused, thought deeply and quickly, and replied.

"Yes I was wounded, seriously wounded but not a wound that anyone could see and fix." His question gave me pause to quickly think about warriors in all the wars that have been fought, including mine, whose wounds were unseen, untreated and debilitating even though no blood was shed.

I spent a sleepless night wondering if my answer had satisfied him...or me. What was there about my military service that left me so hopeless and so helpless when I returned home to civilian life? Was it me? The military itself? The combat? This is what I recalled; perhaps the answers would come as I wrote my experiences down.

To Warriors of all Wars

warriors, combat,

17000

This book is a direct outcome of the noble work of the award-winning filmmaker David Lynch and the David Lynch Foundation. David learned the Transcendental Meditation® technique in 1973 and established his Foundation in 2005 to ensure that anyone suffering from traumatic stress who wants to learn to meditate can do so. In the past five years the David Lynch Foundation has provided scholarships for more than 150,000 people—including veterans and students—to learn the TM® technique and thereby reduce stress, improve health and creativity, and promote inner peace.

After the tragic suicide of a close friend’s son, a young man named Dory Klock who served eight years in the Army, I approached my dear friend Bob Roth, who is executive director of the David Lynch Foundation.

It has been said that the only warriors who do not suffer after being in combat are those who were killed. I cannot attest to that for all battle-tested warriors, but I certainly can for one—me.

Chapter 1:

My War

I was seventeen on December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. It felt as if someone had invaded my home, and I had to do something about it. Two months later—on my eighteenth birthday, February 15, 1942—I enlisted in the Army Air Corps as an Aviation Cadet in waiting. In August 1942, after taking all of the examinations, physical and mental, I was inducted into the Army Air Corps. My training took me to Nashville, Santa Ana, Thunderbird Field in Phoenix, Marana Army Air Base in Tucson, and Luke Field in Phoenix, where I graduated as a fighter pilot in August 1943. I joined the 78th Fighter Squadron on Oahu in October 1943.

I quickly became familiar with death. In December, Bill Sutherland, the CO of the 78th, was killed in a midair collision with Howard Edmondson. Edmondson was killed a few months later when he flew his plane into the sea. Ed Green lost his life when he couldn’t pull his P-47 out of a flat spin, and both Bob Ferris and John Lindner died when their P-51’s exploded over Bellows Field. I attended services for all five of my friends and squadron mates. I mourned their losses but never thought it could happen to me.

On March 7, 1945, our squadron landed on Iwo Jima, on a dirt runway at the foot of Mount Suribachi. I looked out at the landscape as I taxied my P-51 Mustang to our parking area, and saw huge piles of dead Japanese soldiers being pushed into mass graves. The sight and smell is indelibly imprinted on my mind. It was a shocking sight for a young man to see as he entered his 21st year.

The fighting had been fierce on this eight-square-mile island, 650 miles from Japan. Twenty-one thousand Japanese soldiers lost their lives there. Our squadron area was next to a Marine mortuary where hundreds of dead Marines were being readied for burial, a ritual that continued until the remains of nearly 7,000 American Marines were buried in the cemetery.

I flew nineteen long-range missions over Japan from Iwo Jima, flying with eleven other young pilots, all of them friends, who did not return home.

Fred White bailed out of his P-51 on April 12, 1945, and his parachute did not open. Lee Barghaer lost his life when the Japanese exploded a device under his plane as he strafed the runway at Chichi Jima. Dick Schroeppel was hit when he was following me on a strafing run on the airfield of that small island 100 miles from our base on Iwo. He bailed out, ran to the coastline, swam out to sea and climbed into a large lifeboat that was dropped by a B-17. Mortar fire got him and the boat was sunk by rockets with his body in it.

On May 30th, 1945, I shot down a Zero over Tokyo. My wingman, Danny Mathis, also hit the Japanese plane, and we were each credited with half a kill.

I had a toothache when we landed back at Iwo. I ended up having my four wisdom teeth pulled, and I was grounded. Danny was assigned my plane, Dorrie R, and my spot for an escort mission over Osaka on June 1. The squadron took off early in the morning. An hour after takeoff they were led into a huge weather front by the navigating B-29. In the clouds a few pilots spun out and knocked twenty-seven fighter planes out of the sky like bowling pins. Twenty-five pilots were killed, including Danny in my plane, and Jack Nelson from the 78th.

Jack Wrightman crash landed his P-51 in Japan, was captured and died of a broken back in Kempai Tai, a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. His classmates, Wightman and Wayland, also died in combat over Japan.

On July 8, 1945, Al Sherren, my classmate from flying school, called in, “I’m hit and can’t see,” and he was gone. Robert “Pudgy” Carr also disappeared on that day. He was my tent mate.

I learned about the bombing of Hiroshima when I returned from an eight-hour mission on August 6, 1945. Phil Maher jumped on my wing and shouted, “It’s over, one bomb, one city, and it’s over.” I thought he was crazy but it was true. Hiroshima was gone. No more guys getting killed, no more butt-breaking eight-hour missions. And our motto “Back Alive in ’45” would come true.

But it wasn’t to be. On August 13th a mission statement was posted on the bulletin board: Take off tomorrow, August 14 at 0700, for a fighter sweep of airfields near Tokyo.

At the afternoon briefing, Jim Tapp, our Commanding Officer and the Squadron leader for the 14th was asked, “How come another mission, sir?”

“We have to keep them honest,” Tapp replied. “We know the war is almost over. Preparations have been made to abort should that happen during the flight up or on the mission itself, and it probably will. B-17’s and Navy destroyers will be in place to broadcast the codeword ‘Ohio’ on the entire route to Japan. When we hear it we’ll do a 180 and return to Hotrocks”—the code word for Iwo Jima.

Phil Schlamberg, 19 years old from Brooklyn, was assigned to my wing in Blue flight. He leaned over to me during the briefing and whispered, “If I go, Captain, I won’t come back.” Startled, I asked, “Why?” “Just a feeling,” he replied.

After the briefing, I told Tapp what Phil had said. “I don’t have a replacement for him, Jerry,” Tapp told me. “Only Doc Lewis can get him off the mission, but Schlamberg will have to agree to see him.”

“No way. No way will I see Doc,” Phil said, quite emphatically.

Just before takeoff the next morning I told Phil, “Just stick close on my wing. Don’t even think of moving away from a tight position. We’ll be okay. It will be over before we reach the target.”

No one heard the codeword “Ohio” on the flight to Japan, or when we reached the coast and had to drop our external wing tanks. We dropped our tanks, found our targets, and strafed the airfields. We needed ninety gallons of fuel to return to Iwo from Japan. When someone called, “Ninety gallons,” we formed up, and headed out to sea and to our navigating B-29. Phil was tucked in close on my wing. I looked over, gave him a “thumbs up,” and led the flight into some clouds. When we came through the clouds Phil was gone. No radio contact, no visual sighting, just gone.

When we landed on Iwo we found out that the war had been over for three hours, while we were still fighting. Phil Schlamberg must have been the last man killed on a combat mission over Japan in World War II. He didn’t have to die.

Chapter 2:

Discharged

I returned home to New Jersey in December 1945. I reported to Fort Monmouth in Eatontown, New Jersey, where I was given a physical, handed my discharge papers, and sent home to Hillside. I was a former Captain, combat squadron leader, and fighter pilot. But now, emotionally I was just a 17-year-old high school graduate. I was a lost soul, with no one to talk to and no real life experiences to fall back on.

Just after Christmas, I drove to Brooklyn, New York, to meet Phil Schlamberg’s family and to bring them Phil’s wings and Lieutenant’s bars. Phil’s mother didn’t want to meet me, but his sisters did. I gave them his possessions, told them what a wonderful guy he was and how he died. It was heartbreaking for them and difficult for me, very difficult. When I was saying goodbye, his mother looked at me and said, “It should have been you who was killed, Captain, not my son Phillip. I hope you never sleep another night in your life, like I can’t.”

I sat on their front stoop as the snow collected at my feet for an hour before I could get up and leave their house.

For two years I had been a valued member of a large team with only one purpose—to win the war. Four hundred men, working their specialty—armorers, radiomen, crew chiefs, parachute riggers—all with one goal, keeping 30 to 35 airplanes in perfect flying condition so we fighter pilots could take them into combat. Every day we knew what we were doing and why. The pilots were the stars, the chosen few. The missions were long; the highs were higher than anything anyone could imagine. The camaraderie, our purity of purpose, even the danger never clouded our vision.

I had been living with warriors for a long time. We ate together, played together, trained together, and, for a few of us, flew together. Our days in training were long and fruitful.

Our goal as a squadron was to build confidence in our abilities, learn the complexities of our airplane, and become a working unit that would hold up in combat with our enemy.

Individual mentality became team mentality. Single-engine fighter pilots had a lot of freedom when they flew their high-performance airplanes. But that freedom of thought and action had to be molded into a functioning unit if we were to be successful. Hours of formation flying, doing sixteen-plane aerobatics, loops, and slow rolls, made us comfortable with each other. It was a learning experience like none other.

I learned a lot about myself. My abilities to fly an airplane grew exponentially with every hour in the sky. In time I became an element leader, a leader of a two-man flight that was half of a four-man team working the sky together as part of a sixteen-airplane squadron. We were highly trained fighter pilots looking for action every time we left for a mission over Japan.

That the 78th Fighter Squadron, my squadron for two years—the only squadron I ever flew with—was the best, was unquestionable. Then in one minute it was over. The war ended; our reason for living was gone.

Life for me from 1946 to 1975 was empty. The highs I had experienced in combat became the lows of daily living. I had absolutely no connection to my parents, my sister, my relatives, or my friends. I listened to some of the guys I knew talk about their experiences in combat, and I knew they had never been in a battle, let alone a war zone. No one I knew who had seen their friends die could talk about it. I wasn’t interested in going to college, even though it was free with the G.I. Bill. The Army Air Corps had trained me and prepared me to fly combat missions, but there was no training on how to fit into society when the war was over and I stopped flying.

I met my future wife, Helene, on Good Friday in 1949. We were engaged on Memorial Day, and married on October 22. Her parents furnished an apartment for us in West Orange, New Jersey. I commuted to New York where I worked for her father, and hated every day. My escape was golf, an escape I desperately needed. Our first son was born in November 1950 and our fourth was born in August 1960. But I couldn’t find contentment, any reason to succeed, any connection to anyone that had meaning or value. I was depressed, unhappy, and lonely even though surrounded by my family.

That feeling of disconnect, lack of emotions, restlessness, and the empty feeling of hopelessness lasted until 1975. I heard words that described my condition as “battle fatigue” or “shell shocked.” Now that condition is known as “post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).” Every soldier who has been in combat lives with his memories, and suffers silently.

One afternoon in 1975, Helene was watching the Merv Griffin Show on television. Merv’s guest that day was Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, a teacher from India who brought Transcendental Meditation®, an ancient form of meditation, from India to the United States. Helene was fascinated and wanted to learn more. Her search led her to a Transcendental Meditation Center in North Miami Beach, Florida. Excited, she expressed her desire to learn TM to our second son, Steven, who had just graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. Steven was on the Penn tennis team, and the team was leaving for a series of matches in England, so he asked Helene to wait to learn to meditate until he came back in late June.

Both Helene and Steven learned Transcendental Meditation in August 1975, and I learned one month later. It was the beginning of a huge metamorphosis in my life. After a few weeks of twice-a-day meditations, my attitude toward myself began to change. I felt a connection to my inner self. My anger and restlessness began to dissipate, and a calmness that I never knew before became apparent, not only to me but to my family as well. As time progressed I found myself thinking differently about the world around me, and found a direction that had been missing in my life. I welcomed the change eagerly, and TM became part of my routine every morning and every evening. I have been doing it now for thirty-five years. It saved my life.