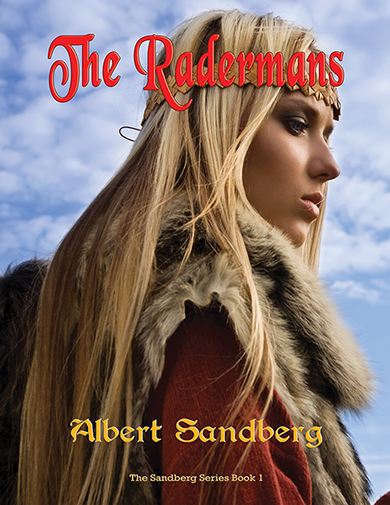

The Radermans

Albert Sandberg

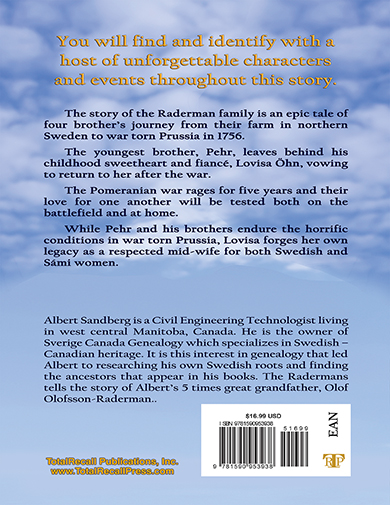

Albert Sandberg is a Civil Engineering Technologist living in west central Manitoba, Canada. He is the owner of Sverige Canada Genealogy which specializes in Swedish – Canadian heritage. It is this interest in genealogy that led Albert to researching his own Swedish roots and finding the ancestors that appear in his books. The Radermans tells the story of Albert’s 5 times great grandfather, Olof Olofsson-Raderman.

The story of the Raderman family is an epic tale of four brother’s journey from their farm in northern Sweden to war torn Prussia in 1756.

The youngest brother, Pehr, leaves behind his childhood sweetheart and fiancé, Lovisa Öhn, vowing to return to her after the war.

The Pomeranian war rages for seven years and their love for one another will be tested both on the battlefield and at home.

While Pehr and his brothers endure the horrific conditions in war torn Prussia, Lovisa forges her own legacy as a respected mid-wife for both Swedish and Sámi women.

Unforgettable characters and events throughout the story.

The story of the Raderman family is an epic tale of four brother’s journey from their farm in northern Sweden to war torn Prussia in 1756.

The youngest brother, Pehr, leaves behind his childhood sweetheart and fiancé, Lovisa Öhn, vowing to return to her after the war.

The Pomeranian war rages for seven years and their love for one another will be tested both on the battlefield and at home.

While Pehr and his brothers endure the horrific conditions in war torn Prussia, Lovisa forges her own legacy as a respected mid-wife for both Swedish and Sámi women.

Unforgettable characters and events throughout the story.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Lisbeth Hilberer

Pomeranian War, Västerbotten regiment, Överstelieutnant Company.

94000

You will identify with a host of unforgettable characters, and events throughout this unique and passionate story.

Chapter 1

Hössjö

June 1756

Olaus Jonsson opened his eyes not knowing what woke him or what time it was. June in Northern Sweden was dominated by sunlight in all but a few hours each day. Born in the fall of 1695, Olaus became Soldier Raderman in his eighteenth year. Now sixty-one and with hearing damage from many years of artillery and musket barrages, he began to wonder if it was, in fact, a noise that woke him. But there it was again, a distant sound, a creak of a wheel turning. He glanced at his sleeping wife, Anna, before quietly slipping out of bed and lifting a corner of the heavy window curtain to peer through the green hued window glass.

"What is it, Olaus?"

"Looks like Jakob and Manni, and maybe Pehr, about half a mile away."

Anna immediately threw back the bed covers and scurried out of the bedroom, "I’ll make breakfast!" she said excitedly.

Olaus and Anna lived with their eldest son, Olof, in the local soldier's croft cottage. The cottage was supplied by the local rote. Usually, four farms constituted a rote under Sweden's soldier allotment system. By providing a soldier with a cottage, a small tract of land, some livestock, and a modest salary, the local farmers were spared military duty. When Olaus retired from the army, his son, Olof, enlisted and became the croft's soldier, inheriting the title Soldier Raderman. In all, four of Olaus's sons

became soldiers of the crown. The reason so many sons became soldiers was probably because of the respect shown to their father for his service with the Caroleans in the Great Northern War and the fact that he survived the death march of 1719. In that war, Sweden fought against a coalition of Russia, Denmark-Norway, and Saxony-Poland-Lithuania from 1700 to 1721.

The Raderman home was one and a half stories, constructed of thick, hand-hewn logs, and measured twenty-eight feet wide by twenty feet deep. There was a bedroom, a chamber room, a cooking and eating area, a back porch and a front deck. The chamber room was once a cowshed, then a small bedroom, and now a bath chamber, complete with a ‘slop pail.’ The slop pail was a larger version of a chamber pot. The half story was an open loft bedroom where Olof slept. Olaus took off his homespun nightshirt and pulled on his trousers and shirt. The woolen fabric was woven by his wife on her loom. The loom, and her spinning wheel, were products of Olaus’s carpentry skills and were a source of pride for Anna.

Today, some of Olof's brothers were coming to help build a small outbuilding to be used as sleeping quarters for Olaus and Anna. Olof is to be married in the fall and will need the extra room, and the added privacy, to start his own family. He and his father had helped their neighbor, Öhn Larsson, clear a forested parcel of land the previous fall and had accepted the felled spruce logs in payment for their labor.

Olof was standing on the small front deck watching his approaching brothers when Olaus came out of the cottage. Apart from age, Olof and Olaus were strikingly similar in appearance. Both were wiry and 5’8” tall, both sported bushy mustaches, and both had the same rolling walk and mannerisms. Olaus, however, had graying hair and a ruddiness to his cheeks, some say from his fondness of his homebrew, but more than likely, it was the effect of severe frostbite suffered during the Great Northern War. Standing on the deck, Olaus looked across the packed earth farmyard at the approaching wagon. To his right stood their barn, constructed out of log, as with all their buildings, and a loft complete with a hay hood and wooden pulley for hoisting hay bundles. Connected to one side of the barn was a pole and willow chicken pen and to the other, a pole corral for their sheep. Each of these pole structures had a small door for the chickens and sheep to go in and out of the barn. On the other side of the farmyard were their firewood and storage sheds. All the buildings were unpainted, peeled logs, aged to a dark brown with end rafters that formed an X above the roof’s peak. The tops of the roofs were covered with birch bark and sod. The grass varied in length from three to eighteen inches. Behind their cottage were a small garden, and their outhouse. Around the perimeter of their farm was their gärdsgård, a six-foot high fence with pairs of upright poles pounded into the ground at twelve-foot intervals and bound together with willow. Between the upright poles were horizontal poles about fourteen feet long, each overlapping the next set of poles so that they lay at a slight upwards angle.

Jakob, 24, and Emanuel (Manni), 20, were assigned to neighboring rotes, Jakob became soldier Wennström at Kasamark and Emanuel, soldier Apelfeldt in Brattby. Upon entering military service, each recruit was assigned a new name. This practice was necessary due to the Swedish patronymic naming system where the child's surname would consist of his or her father's first name, followed by son or dotter. So, all of Olof's sons would have the surname Olofsson, and all his daughter's surnames would be Olofsdotter. This did not work so well in the military as there would be many Lars Larssons, Olof Olofssons, Sven Svenssons, and so on. Hence, the regiment's commander would assign a new surname to new recruits. The assigned surname may be based on where they were from, their physical attributes, or their trade. Names such as Berg (mountain), Stark (strong), Svärd (sword), Björn (bear), or Lång (tall) were common. Upon recruitment, Jakob and Emanuel assumed the names of their respective rote farms.

Aside from maintaining his farm, Emanuel also worked as a woodcutter in Brattby. He had purchased an old draft horse and wagon from one of the rote farmers the year before, so he could haul the logs he cut. Emanuel was a stocky man, standing 5’7”. Pehr, Olof's youngest brother, was walking alongside the wagon, having met up with Jakob and Emanuel not far from the Raderman farm. Pehr, nineteen, was soldier Rask housed near the small village of Bösta. Pehr was the same height as Emanuel but did not have the corded muscles of his brother. Jakob, on the other hand, stood 6’1” with wide shoulders and always relished a good fight. Pehr and Jakob where the only sons that inherited their mother’s blond hair and blue eyes. The rest of the brothers, and Olaus, all had brown hair and brown eyes.

"Hej [Hello] Pappa, Hej Olof!" called Emanuel.

"Välkommen [Welcome]!" Greeted Olaus, "Come on in. Olof will put up your horse."

"Ja [Yes], and I will have a look at that axle," Olof said. "That wagon squeals like Pehr when he sees a mouse!"

They all brayed laughter. Even Pehr laughed good-naturedly. Some say that when Olaus and all his sons laugh together, the sound is likened to a flock of excited geese.

Anna, standing before the open fireplace, stirring the porridge, smiled when she heard the laughter. She was fifty-eight and stood 5’5”, a little overweight, but her physical stature belied the fact that she was the undisputed ruler of the Raderman family. The interior of the cooking and eating area was dark with aged wood surfaces, log walls, pole and plank ceiling and plank floors, and wood furniture. The two south-facing windows allowed some light in through wavy glass panes. Of Anna’s eleven children, only Olof remained on the farm. Two girls and one boy had died in infancy of the fever, three daughters were married and starting their own families, one son was married and renting a farm near Vännäs, and, of course, the three sons coming today. All were born and had lived their young lives in this small, log cottage. She marveled at how they had all fit in here. With a sigh, she remembered the laughter, tears, roughhousing, good meals, and hunger that had taken place in this cottage. Each of her children, and Olaus, were taught to read and write by Anna, who was taught by her father, a Lutheran pastor from nearby Bösta.

The men coming inside brought her out of her reverie, and she rushed to greet her sons, wiping her hands on her apron.

"Hej Mamma!" Jakob, Emanuel and Pehr said in unison.

"My boy," she said to each, as she hugged them.

"Sit, sit," she said, as she ladled porridge into bowls and handed them to Olaus to place on the heavy birch table. The table and chairs were Olaus’s handiwork and were built with a sturdiness that would far outlast any furniture sold in the shops in Umeå, or Stockholm for that matter.

Pehr reached across the table and took a piece of knäckebröd, thin hard rye bread, broke it into small pieces, and stirred it into his porridge. Jakob and Emanuel shared a glance and made a point of each biting off a chunk of the bread and chewing loudly. This earned a withering look from Anna. Pehr, who was smaller in stature than his brothers, also had a slight effeminate side that enamored him to his sisters and mother. Growing up, his brothers faced the wrath of their sisters if they bullied Pehr. Pehr was oblivious to all this, or so it seemed, and would often be found helping the women preparing meals or cleaning the cottage while the other boys were out doing their chores. The entire family was taken aback when Pehr announced he was enlisting as a soldier. While his brothers heartily slapped him on the back, almost knocking him over, his sisters decried his decision. Anna, on the other hand, knew the real reason; Pehr enlisted to impress his big brother Jakob.

Olof washed his hands in the porch's washbasin and walked into the cottage, drying them on his shirt.

"Tack [thank you], Mamma," he said, accepting the bowl of porridge and sitting down at the table. "We need to repack that front wheel, Manni, it's loose and has lost most of its tallow."

"Ja, I hit a hole a few miles back; that's when it started squealing," said Emanuel.

"I see you brought some planks with you," said Olof.

"Ja, I cut some extra when I was doing some milling for a neighbor."

"That is good, Manni!" Olaus exclaimed happily.

"Is Lovisa coming?" asked Pehr.

This elicited a lot of oohing and kissing noises from his brothers.

"Boys! Stop teasing Pehr!" admonished Anna.

"She said she might come by if her father lets her," she said to Pehr.

Lovisa and her father were neighbors to the west. Her demeanor was that of a tomboy; the opposite of Pehr. She preferred to be out working with the men than to be inside cooking or sewing. She became known as Lovisa Öhn rather than the typical Öhnsdotter because the parish priest would often mistakenly write down her name as Lovisa Öhnsson during the annual household examination. When he was informed of the mistake, he would impatiently scratch out the "sson" portion, leaving it as Öhn. And thus, she became known as Lovisa Öhn. Lovisa and Pehr had been inseparable from a young age. She would often be involved in a knockdown, drag-out, rolling in the dirt fight with local bullies who made the mistake of picking on Pehr in her presence. This had endeared her to Pehr's mother and sisters. His brothers, not so much, but they did have a grudging respect for her.

Olaus pushed back from the table and announced, "Time to start work, boys!" And, with a chorus of chair legs scraping across the plank floor, they stood and filed out the door.

"Who wants to notch the logs?" he asked loudly when they got to the stacked logs.

"I will!" Lovisa called, as she came through the bush trail connecting her farm with the Radermans. She was a slim girl standing 5’6” with blond hair, blue eyes, and freckles.

"Löva!" called Pehr, running to pick her up in a hug and swinging her around.

"Pehr, put me down!" she shrieked, but she did have a big grin on her face. Pehr was the only one she allowed to call her Löva; or to swing her about, for that matter.

"Okay Lovisa, you can notch," said Olaus. He had seen examples of her work on some of the outbuildings at Öhn's farm and had been impressed with the tight-fitting joints. The previous fall, Olaus and Anna had set the foundation with fieldstones, while Olof had squared the logs with his broad-ax. And now, they soon fell into a pattern; Jakob and Olof carrying the logs to the foundation, Lovisa deftly chopping the corner x-joints, while Emanuel and Pehr lifted and moved the logs as she directed. Emanuel didn't mind being told what to do by a girl, not when she was doing such quality work. Olaus was clearly enjoying his role as supervisor. They worked all morning steadily only to pause now and then to go to the rain barrel for a ladle of water, as it was a warm day, to drink and to pour over their hair. The fact that the water poured over their sweaty heads would fall back into the barrel for the next person to drink didn't seem to enter their thoughts.

"Pehr, come help me with the table," called Anna.

"Ah, lunch!" Pehr said as he stretched his back and headed off to the cottage.

Pehr helped Anna carry the food out to the outdoor table. Pickled herring, turnips, knäckebröd and lingonberry jam made up the midday meal, with warm ale and cider to drink. The outdoor table was rougher than their inside table. The legs were in an x-shape with cross beams and rough planks on top. The seats were long benches, heavy planks nailed to tree stumps. Many a painful splinter ended someone’s meal. The table was twelve feet long to accommodate guests and sat below a large birch tree.

"Pehr, go tell them lunch is ready."

"Lunch is ready!" yelled Pehr, at the top of his lungs.

"Ach, I could have done that!" she said.

"Nej [No], we tend to run the other way when you yell."

Anna had to laugh at that; Pehr always could make her laugh.

Before being allowed to sit at the table, they all had to go to the deck water basin and wait their turn to wash up. The deck was low to the ground, at door sill level and ran from the door to the western end of the cottage. A small stand with an enameled metal bowl sat at the end near the water barrel. Two chairs sat on the deck where Olaus and Anna would sit and drink their tea in the evenings.

Out of deference to Lovisa, they let her wash first. She took her time, trying to scrub the spruce gum off her hands and forearms, while the men patiently waited. Giving up on that futile task, she splashed water on her face and pressed a finger to one nostril, blew out water and mucus into the basin, and repeated the process with the other nostril. This brought yells of protest from Olaus and his sons, as Lovisa bent over laughing and jumped out of Jakob's reach, as he took a swat at her. Lovisa had a nasal staccato laugh usually followed by an involuntary nose snort.

"Jakob! Just dump the water and refill the basin!" called Anna.

After they had all washed and sat down to eat, Olaus said, "That was good work cutting the joints, Lovisa."

"Tack, Pappa," replied Lovisa. She had, many years ago, taken to calling Olaus and Anna Pappa and Mamma, and they also took her as family.

Emanuel was the last to come to the table. He had walked over to the barn to see to his horse. Emanuel had a way with animals; he seemed able to communicate with them. Once, when he was ten, Olaus had taken him along to visit the Sámi who were herding reindeer toward their winter pasture. Olaus went there to barter for winter meat. He had brought along some old tools he had bought from a peddler for this purpose. Upon arrival, Olaus was met by the tribal elder, Antte, and they exchanged greetings. The Sámi and the Swedes had been trading since the Viking age and, over time, have borrowed words and phrases from each other’s language to a point where they could easily understand each other. They sat down, cross-legged, on a reindeer hide to begin the bartering, Emanuel wandered over to where the herd of reindeer was grazing. He walked right up to a large, snorting bull and stood nose to nose with the animal. Antte looked over, jumped to his feet, and crept slowly toward Emanuel and the bull. The beast, sensing the movement, broke eye contact with Emanuel and trotted off to where the rest of the herd had gathered.

"That boy has a gift, Olaus. That bull is very dangerous. Always have to watch him."

"Ja, it's like he can talk to animals with his eyes," replied Olaus. The barter was made, and a reindeer cow was slaughtered. Emanuel had cried quietly all the way home while turned around on the wagon's seat and looking down at the reindeer's sightless eyes.

"The walls are going up fast," commented Emanuel. "Those joints look tight, Lovisa."

"Ja, she does good work," Olof added.

"Ach, it is nothing," Lovisa said, but her face flushed, and she visibly swelled with pride. Pehr noticed this and playfully gave her shoulder a shove. Of course, she could not let that go unpunished, so she shoved back, and they shoved back and forth all smiles and giggles. "You two stop that!" commanded Anna. "Eat your food!"

After their midday meal, they went back to work on the new cottage. Emanuel and Pehr would straddle a log, bend over, and be ready to lift or turn it when Lovisa directed them to. Lovisa was bent over chopping the x-joints into the ends of the logs. It so happened that Emanuel's face was close to Lovisa's rear end when she let loose with a long and resounding fart.

"Förbaske! [Dammit]," yelled Emanuel, as he straightened up and backed away.

"Sorry, Manni. Too many turnips," Lovisa said, which caused Pehr to burst out laughing, which caused Lovisa to burst out laughing. And as she laughed, an occasional "brrrip" would escape her, which started more gales of laughter.

"Förbaske!" repeated Emanuel as he stormed off toward Olof and Jakob who were busy wrestling a log off the pile. After a short conversation and a few more laughs, Jakob came over to Pehr and Lovisa.

"Manni and I traded places," he said, "but I will be on that end of the log," pointing to the opposite end of which Lovisa was working on. They made good progress with the walls, ending the day at about three feet high.