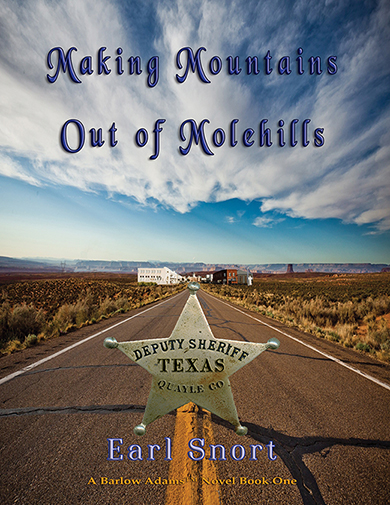

Making Mountains Out of Molehills

Earl Snort

Earl Snort is the nom de plume’ of a retired law enforcement officer with more than forty years’ experience toting a badge and a gun.

Before that, he served in the armed forces.

He and his wife have been married nearly fifty years. They reside in the South. They have one son, also a career law enforcement officer, and two grandchildren.

This is the author’s first foray into the world of writing fiction. After a lifetime of writing non-fiction to document investigations of true crime, he decided to try his hand at make believe.

He hopes you enjoy the yarn.

May 26, 2019

This is the story of a young man becoming a lawman in the 1960's, an era which has long been forgotten except for those who lived it.

It was 1969. Barlow Adams, age 20, was a recently discharged veteran. He was driving late at night on a lonely stretch of highway in the Trans-Pecos region of Texas. He stopped to render assistance to a motorist with a flat tire. What he stepped into was a vicious attempted rape. He rescued the victim, which catapulted him into an appointment as a deputy sheriff.

Along the way he encounters an enchanting woman who will change his life forever. In addition, he will be confronted by a gang who is obsessed with killing him. Will they succeed?

“This is dedicated to the one i love.”

-- Mamas & The Papas - 1967

“Oh, my love, my darling, i’ve hungered, hungered for your touch,

A long, lonely time.”

-- Unchained Melody

- The Righteous Brothers - 1965

lawman, law enforcement, vetran, texas, rape

91000

This is the story of a young man becoming a lawman in the 1960's, an era which has long been forgotten except for those who lived it.

CHAPTER 1

POST HIGH SCHOOL DILEMMA

W

ednesday, June 18, 1969. Corporal Barlow K. Adams, Army of the United States, was peering out the window of the back seat of a Greyhound bus while it cruised the highway from Junction City, Kansas, en route to Arlo, Texas, and beyond. He was attired in his dress green uniform, with an array of three ribbons on his left breast.

The one nearest to his heart (red and yellow) was the National Defense Service Medal, awarded by the United States to military servicemen on active duty for at least six months during wartime.

The middle ribbon (yellow, red, and green) was the Vietnam Service Medal, bearing three small bronze stars. It was awarded by the United States to armed forces personnel who served in Vietnam from 1965 and continuing. The small bronze stars were awarded for participation in three of the nine campaigns which had taken place since the onset of the war.

The ribbon nearest his arm (green and white) was the Vietnam Campaign Medal, which was awarded by the Republic of Vietnam to military servicemen who served in the Vietnam War.

Centered below the ribbon bar was an Expert Rifleman’s Badge. It consisted of a silver Maltese cross, centered with a three-ring bullseye, and bordered along the sides and bottom with a semi-circular wreath. A silver bar attached by small loops on the bottom read, ‘Rifle.’

The biceps area of both sleeves bore two, inverted, gold chevrons, representing the rank of corporal, the lowest of the non-commissioned officer ranks.

On the right sleeve, near the cuff, were two, small, horizontal stripes, each stripe representing six months of overseas duty.

On the right sleeve, just below the shoulder seam was the circular red, white, and blue sprocket patch of the 9th Motorized Infantry Division, representing the unit with whom he served in combat in Vietnam.

On the left sleeve, just below the shoulder, was the olive drab, pentagonal patch bearing the red numeral one, representing the 1st Infantry Division in Fort Riley, Kansas, to whom he was currently assigned for 25 more days while he was on terminal leave before ETS (completion of his enlisted time in service.)

His circular brass lapel insignia depicted the crossed tubes of old-time cannons, representing assignment to the field artillery on one side, and ‘U.S.’ on the other. In fact, Corporal Adams was an assistant gunner on a 105-millimeter howitzer.

The miles passed slowly, but Barlow was in no hurry. He daydreamed about the odyssey which carried him to this point. Two years past, he graduated from Benson County High School in Baileyville, smack in the middle of the Texas panhandle, with no promising future in sight.

At age 12, his parents were killed in a fiery crash when a church bus crossed the centerline of Texas Highway 114, crashing into his parents’ station wagon head-on. They were returning to Arlo from Baileyville on a Wednesday night, after competing in a bowling tournament. Both vehicles were estimated to be traveling between 50 and 60 miles per hour. The bus driver apparently suffered a heart attack and lost control. Six people, including his folks, were pronounced dead at the scene. Another fifteen were seriously injured. It was the worst traffic accident in Benson County history.

Barlow, who was in the seventh grade, and his sister, Chloe, who was seventeen and a senior in high school, went to live with his Grandma Bea, who lived four doors down. Chloe graduated and moved to Canyon, just south of Amarillo, to attend college at West Texas State University. She graduated while Barlow was in the 11th grade. She married Bert Kilgore, another WTSU graduate, as well as a member of the U.S. Air Force Reserve, who became a life insurance salesman. They moved to Bisbee, Arizona.

In the eighth grade, Barlow began working part-time at his Uncle Clive’s Sinclair gas station after school, and essentially full-time during the summers. Uncle Clive made more money servicing cars than he did selling gasoline, and over the years, Barlow became a proficient auto mechanic. He didn’t know what he wanted to do ‘when he grew up,’ but he did know he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life under a car on a creeper or slumped over an engine.

On June 1, 1967, Barlow graduated from Benson County High School. The next day, his draft board classified him I-A, available for military service. He had to make an occupational decision very soon, or the decision would be made for him.

The Vietnam War was in full swing, essentially leaving him with two options. Fleeing to Canada as a draft dodger was not one of them.

Option One was, he could attend college on a II-S student deferment, valid for a maximum of four years until graduation. If he quit or flunked out, he would be reclassified as I-A. If he graduated, he would be reclassified as I-A. Either way, all he could hope to accomplish, would be to postpone the inevitable military service, unless the war ended, which did not appear to be on the horizon.

Option Two would be to join the armed forces. Actually, that sort of appealed to him. His dad was a World War II Army vet. He served in the military police in Europe with the 3rd Division. It would be nice to get paid to see the world, although today, it appeared the most likely destination for a serviceman would be Vietnam.

He checked. The Air Force, Navy, and Coast Guard all required a four-year commitment. The Marine Corps and Army both required a three-year commitment.

The National Guard and all the reserve components required a six-year commitment. Of course, all the reserve units he knew about were full or nearly full because folks were trying to avoid Vietnam. You had to have a hook to get in. Even then, it was not a ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card. He knew of a Texas Army National Guard unit deployed over there, and several guys from his high school who were in the Marine Corps Reserve had been deployed.

There was one other solution to Option Two. He could sign up for the draft, which was only a two-year commitment. Of course, he would forfeit all rights to choose a career field or a first post of duty, and he’d heard that in some instances, draftees were placed in the Marines. Barlow would rather be in the Army, but the obligation was for only two years. He decided to ‘roll the bones.’

On Friday, June 9, 1967, Barlow signed up for the draft.

On Tuesday, July 13, 1967, Barlow was inducted into the Army of the United States, the organizational designation for draftees, not to be confused with the U.S. Army, or the U.S. Army Reserves, or the Army National Guard, all of whom wear the same uniform, and all of whom attend the same basic combat training (BCT.) The only distinction Barlow could discern, besides the reduced term of commitment, is that some of the drill instructors (DI’s) in BCT seemed to hold draftees in contempt.

Truth is, the DI’s weren’t much friendlier to the national guardsmen or reservists. What they did, was to shame Regular Army (RA) trainees who were beaten in combat training competition by one of the draftees or weekend warriors. Then both victor and vanquished suffered by doing more push ups, etc. There was no way to win.

God had a guardian angel looking over Barlow and he knew it. The Army sent him to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for BCT and advanced individual training (AIT) as a field artilleryman. The training was long - six months before he graduated from both schools. He was given a two-week leave before shipping out to the Republic of Vietnam, where, on January 29, 1968, he was assigned to C Battery, 1st Battalion, 11th Artillery, 9th Motorized Infantry Division, in III Corps Tactical Zone at Fire Support Base Danger in the Dinh Tuong province for a 12-month deployment.

The enemy’s surprise Tet Offensive began on January 30, 1968. Welcome to Vietnam, Barlow! Great timing! He had a busy tour. He saw more combat than he ever wanted, but less than many others. His tour ended with him injury-free.

One of his battery mates was KIA and four were WIA - five Purple Hearts in all, out of 52 soldiers assigned to Charley Battery simultaneously, assuming they were at full strength. With combat tours being twelve months, over the course of a year, they had at least a hundred percent turnover, since soldiers trickled in and out one or two at a time. Therefore, probably 100 soldiers served in Charley Battery while he was there. With that in mind, their casualty rate was low.

His last five months in the Army were uneventful at Fort Riley. Now he was returning to Arlo, population 1,450, honorable discharge in hand, and a little over $1,800 in his pocket.

Grandma Bea had passed away while he was in Vietnam. Uncle Clive sold her house and moved Barlow’s meager belongings into his own. Chloe and he were included in her will as heirs, receiving $1,000 each. The $1,800 included his inheritance.

CHAPTER 2

RETURNING TO A HOME THAT WASN’T

O

n Thursday, June 19th, after two transfers, he stepped off the bus right in front of Adams’ Sinclair station in Arlo. He enjoyed a warm reception from Uncle Clive and Aunt Marilyn, and both his elementary school-aged cousins. They put him up in the spare bedroom in the attic, where his few belongings were already in place. They said he could stay as long as he wanted.

Uncle Clive had expanded his business to include a used car lot with sixteen ‘pre-owned’ vehicles. (Why didn’t he just call them used cars?) He offered Barlow a job as the salesman, paying a ten percent commission on anything he sold.

Barlow began work in the lot the following day, pondering his next move. It was swell Uncle Clive and Aunt Marilyn took him in and gave him a job. He sincerely appreciated their generosity, but knew he needed something different and more challenging. He just didn’t know what.

He didn’t have many lookers at the lot. In fact, he only sold one car, for which he received a $90 commission. That was about a half-month’s pay in the Army. He had lots of time on his hands, which allowed him to closely inspect all the inventory.

He fell in love with a faded, mint green,1965, Dodge 100, short bed pickup truck. It had a 225 Slant-Six, 145 horsepower engine, with a manual, three-speed transmission on the column, and an AM radio that worked as good as new. It only had 58,000 miles, with no rust or dents. The tires were well worn, and it needed brakes and a tune up. It had never been wrecked. The only drawback was it didn’t have air conditioning. He decided he could live without that.

Eric Stottlemeyer had been the only owner of the truck. Barlow knew him, because he had been Barlow’s 10th grade biology teacher. He also knew Mr. Stottlemeyer would never abuse a motor vehicle. Uncle Clive wanted $800 for it, but sold it to Barlow for cost at $675.

Barlow was busy all the next week. He changed the oil, gave it a lube job, changed the plugs, wires, and points, changed the transmission seals and replaced transmission fluid, put on new brake pads, flushed the radiator, installed a new fan belt, windshield wiper blades, battery, and tires, to include the spare.

Although the seat was in good shape, he purchased an Indian weave seat cover, with an open-ended pouch on both ends which ran the length of the bench seat along the bottom front, to carry his rifle out-of-sight, but easily accessible. He washed, polished, and waxed the truck twice. When he was done, it shined like a jade ashtray. Accordingly, he named his truck Jade.

Barlow settled into a routine similar to his days in school. Benson County High School was thirteen miles east of Arlo in Baileyville, the county seat. He rode the school bus to and fro. He wasn’t allowed to stay after school for clubs or sports, because he worked in the service station on weekdays after school until it closed at 7. He worked on Saturdays from 8 until closing at 5.

On Sundays they attended the Arlo Methodist Church. In the spring and summer, Uncle Clive and he played in the church softball league. Uncle Clive asked Barlow if he wanted to get back on the men’s team, but he declined, stating that for the time being, he had some other things he wanted to do on Sunday afternoons.

For one thing, Barlow needed some time to target practice with his Winchester, Model 1894, lever action, 30-30 caliber rifle. It was a pre-‘64, one of the last manufactured, and had been a Christmas gift from Grandma Bea when he was 14. Uncle Clive liked to deer hunt, and together that became an autumn family ritual. Deer hunting was the single most thing he missed during his time in the Army.

The target practice was pleasurable, but it wasn’t the only thing on his mind. Barlow was restless to hit the road and see something different while he figured out what to do with the rest of his life. Officially, that would begin on July 12th, when his ETS was final.

He could attend North Texas Junior College in Baileyville, in September on the G.I. Bill. He could apply elsewhere, maybe WTSU, like Chloe. Alternatively, he could find a more challenging job, in a career field other than selling or working on cars. The latter two options would disappoint Aunt Marilyn and Uncle Clive, but were he to make a break, sooner would be less painful than later.

Taking a trip to Bisbee to visit Chloe would be the easiest way out. He decided he would take all his personal belongings. This would include a few framed photographs of his parents, Grandma Bea, and Chloe, high school yearbook for 1967, diploma, and other documents, such as his birth certificate and one for perfect attendance in Sunday School his sophomore year, plus the trophy he got in the 6th grade for playing on the Benson County American Legion championship baseball team. They would know he didn’t expect to return, but this way it wouldn’t be necessary to come back and make a hard break even harder, if he did decide to move.

On Sunday, July 6th, he called Chloe to see if a visit would be okay. She joyfully invited him to come for as long as he pleased. That being settled, he said he would see her in a couple of weeks. He spent the following week making preparations.

Barlow had grown the two years he was in the Army. He was 5’9” tall and weighed 140 pounds when he reported for induction. Now he was 5’10” and weighed 165. His waist size had expanded from 32 to 34 inches, but he packed a lot more muscle.

He collected all of his clothes which were too small, and donated them to the Goodwill in Baileyville. Then he stopped at J.C. Penney’s and purchased three pairs of Wrangler jeans, six western cut, long-sleeve shirts, and a blue jean jacket.

Next he went to Cowboy Bob’s Western Emporium and bought a pair of brown, low-heeled, round-toed, Justin cowboy boots with a matching brown belt. He took his time before selecting a beige 7X Stetson, with a medium crown and brim. It was good to be back in Texas.

After that, he went to the Army-Navy store. He bought two Army surplus footlockers - one for clothes and another for personal items. Then he picked through the secondhand Army field gear, selecting an oiled canvas tarp to cover the bed of his truck, two hanks of 500-mile-per-hour cord, a web belt, sleeping bag, two metal canteens with cups and carrying cases, a mess kit, pack, spaghetti straps, entrenching tool, and an M-14 ammo pouch (to hold small items). En route to the checkout counter, he spotted and purchased a metal Stanley thermos.

The final stop was at Johnston’s Gun Shop, where he bought five boxes of 170-grain, 30-30 cartridges, cleaning patches, and a bottle each of Hoppe’s Number 9-gun solvent and gun oil.

He was ready to go. His stash was down to $700. He couldn’t dilly dally for too long before finding gainful employment.